Features

Continuing Education

Education

A Multi-Profession Case Study

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome is a condition that is somewhat controversial. There are varying opinions as to whether such a condition exists. What is certain, however, is that symptoms/impairments causing; pain, altered sensation, weakness and a distress in the region of the thoracic outlet and arm, does exist and clients presenting with this distress require relief.

December 21, 2009 By Massage Therapy Magazine

|

|

|

|

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome is a condition that is somewhat controversial. There are varying opinions as to whether such a condition exists. What is certain, however, is that symptoms/impairments causing; pain, altered sensation, weakness and a distress in the region of the thoracic outlet and arm, does exist and clients presenting with this distress require relief. This discussion was designed to bring about communication with respect to this unique and common group of presentations.

A collection of information describing Thoracic Outlet Syndrome is presented here, followed by information contributed from the perspective of Massage Therapy, Osteopathy, Physiotherapy, Acupuncture, Chiropractic and Yoga (Rehabilitation).

Thank you to all who participated in this special feature.

– Jill Rogers, Publisher MTC magazine.

What Is Thoracic Outlet Syndrome?

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) consists of a group of distinct disorders that affect the nerves in the brachial plexus (nerves that pass into the arms from the neck) and various nerves and blood vessels between the base of the neck and axilla (armpit). For the most part, these disorders have very little in common except the site of occurrence. The disorders are complex, somewhat confusing, and poorly defined, each with various signs and symptoms of the upper limb. [1]

|

|

|

|

Three Definitions

A syndrome is a combination of signs and symptoms that characterizes an abnormal condition. TOS gets its name from the space (the thoracic outlet) between your collarbone (clavicle) and your first rib. This narrow passageway is crowded with blood vessels, muscles, and nerves.

If the shoulder muscles in your chest are not strong enough to hold the collarbone in place, it can slip down and forward, putting pressure on the nerves and blood vessels that lie under it. Symptoms vary, depending on which structures (nerves or blood vessels) are being compressed. Pressure on the blood vessels can reduce the flow of blood to your arms and hands, making them feel cool and tire easily. Pressure on the nerves can leave you with a vague, aching pain in your neck, shoulder, arm or hand. Overhead activities are particularly difficult.

TOS can result from injury, disease, or a congenital abnormality. Poor posture and obesity can aggravate the condition, which is more common in women than in men. Psychological changes are often seen in patients with thoracic outlet syndrome. It is not clear whether these precede the onset of the syndrome or are the result of dealing with the pain and frustration of diagnosing and treating this condition. [2]

The thoracic outlet is an area in the neck above the uppermost rib on both sides of the body. The main artery and vein and the entire nerve supply to the arm are located in this space. This area is just above your collar bone and outside of your front neck muscle. If you put the fingers of your right hand above your left collar bone, you may be able to feel the artery beating. There are several conditions that can cause narrowing of this space. Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) occurs when the narrowing of this space causes pressure on your nerves or blood vessels. Thoracic outlet syndrome can refer to symptoms caused by compression of the artery, the vein, or the nerves to the arm. All types of TOS are caused by bony or non-bony structures pushing against the vein, artery, or nerves, interfering with their normal function. [3]

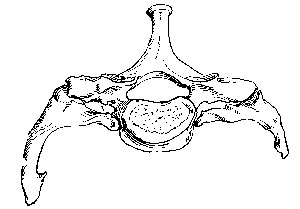

Anatomy

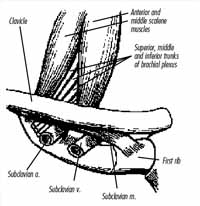

Normally, everyone has 12 ribs on each side of their chest. The first rib is attached to the spine in back and to the sternal bone in front. On the very back part of the rib is a muscle called the middle scalene muscle. This muscle also attaches to the cervical vertebrae.

In front of the middle scalene muscle, five nerves exit the cervical and upper thoracic spine and then cross on top of the first rib and under the collar bone. These nerves are known as the brachial plexus. In front of those large nerves the main artery to the arm – called the subclavian artery – crosses over the first rib. In front of the artery is a second muscle, the anterior scalene muscle. This muscle is connected from the lower cervical spine to the first rib.

Finally, in front of the anterior scalene muscle is the subclavian vein. All of these nerves and blood vessels eventually course under the collar bone and over the first rib. [4] The brachial plexus trunks and subclavian vessels are subject to compression or irritation as they course through three narrow passageways.

The most important of these passageways is the interscalene triangle, which is also the most proximal. This triangle is bordered by the anterior scalene muscle anteriorly, the middle scalene muscle posteriorly, and the medial surface of the first rib inferiorly. This area may be small at rest and may become even smaller with certain provocative maneuvers.

Anomalous structures, such as fibrous bands, cervical ribs, and anomalous muscles, may constrict this triangle further. Repetitive trauma to the plexus elements, particularly the lower trunk and C8-T1 spinal nerves, is thought to play an important role in the pathogenesis of TOS.

The second passageway is the costoclavicular triangle, which is bordered anteriorly by the middle third of the clavicle, posteromedially by the first rib, and posterolaterally by the upper border of the scapula.

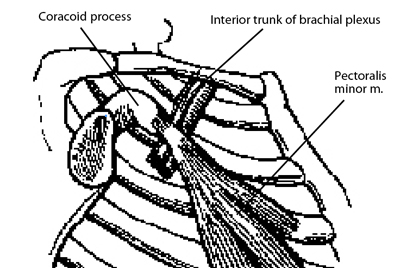

The last passageway is the subcoracoid space beneath the coracoid process just deep to the pectoralis minor tendon.

Types Of TOS (5)

True neurologic TOS is the only type with a clear definition that most scientists agree upon. The disorder is rare and is caused by congenital anomalies (unusual anatomic features present at birth). It generally occurs in middle-aged women and almost always on one side of the body. Symptoms include weakness and wasting of hand muscles, and numbness in the hand.

Disputed TOS, also called common or non-specific TOS, is a highly controversial disorder. Some doctors do not believe it exists while others say it is very common. Because of this controversy, the disorder is referred to as “disputed TOS.”

Many scientists believe disputed TOS is caused by injury to the nerves in the brachial plexus. The most prominent symptom of the disorder is pain. Other symptoms include weakness and fatigue.

Arterial TOS occurs on one side of the body. It affects patients of both genders and at any age but often occurs in young people.

Like true neurologic TOS, arterial TOS is rare and is caused by a congenital anomaly. Symptoms can include sensitivity to cold in the hands and fingers, numbness or pain in the fingers, and finger ulcers (sores) or severe limb ischemia (inadequate blood circulation).

Venous TOS is also a rare disorder that affects men and women equally. The exact cause of this type of TOS is unknown. It often develops suddenly, frequently following unusual, prolonged limb exertion.

Traumatic TOS may be caused by traumatic or repetitive activities such as a motor vehicle accident or hyperextension injury (for example, after a person overextends an arm during exercise or while reaching for an object). Pain is the most common symptom of this TOS, and often occurs with tenderness.

Paresthesias (an abnormal burning or prickling sensation generally felt in the hands, arms, legs, or feet), sensory loss, and weakness also occur. Certain body postures may exacerbate symptoms of the disorder.

Is There Any Treatment?

Treatment for individuals with TOS varies depending on the type. True neurologic TOS is generally effectively treated with surgery. Most other forms need only symptomatic treatment. Common or disputed TOS requires conservative treatment which may include drugs such as analgesics, and physical therapy to; increase range of motion of the neck and shoulders, strengthen muscles, and induce better posture.

Some cases of disputed TOS may require surgery (although, like the diagnosis, surgery is controversial). Heat, analgesics, and shoulder exercises have been used with limited success in individuals with traumatic TOS. Surgery may be needed in some cases. Vascular TOS often requires surgery.

What Is The Prognosis?

The prognosis for individuals with TOS varies according to the type. For the majority of individuals who receive treatment the prognosis for recovery is good. [5]

Medical Approach: Injections & Surgery (6)

In thoracic outlet syndrome, injections are used to diagnose the syndrome and determine which kind of TOS a patient may have. The physician may request a test called an anterior scalene muscle block, which is performed by a qualified physician (usually an anesthesiologist familiar with TOS). The anterior scalene muscle is numbed with a local anesthetic, relaxing it.

If this relaxation improves symptoms for a short time, this tells the doctor that the anterior scalene is either pushing on the nerves or hampering their movement.

Some physicians may request that a local anesthetic and a steroid be placed around the brachial plexus between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. If this relieves symptoms using only small amounts of medicine, it tells the physician that the pain is coming from where the medicine was placed, the brachial plexus.

Other tests can be used to further refine the diagnosis, such as an epidural injection, facet injections into joint spaces in the lateral posterior cervical spine or even a discogram.

Surgery may be an option for patients whose symptoms are not improved with medication and physical therapy. Some studies say that only 10 per cent to 20 per cent of patients need surgery to relieve compression caused by the first rib or abnormal muscles. Surgery can be helpful, but the success rate varies. Some studies suggest that up to 80 per cent of TOS patients who have surgery get pain relief, but other studies put that estimate at 45 per cent.

Decompression surgery for TOS is a procedure in which the surgeon removes all or part of the extra rib, if present, or the first rib. The surgeon also may remove some of the small muscles attached to the rib and any tissue that may be putting pressure on the nerves or blood vessels. [6]

Signs & Symptoms Clinical Presentations (7)

The signs and symptoms that an individual may experience depend on whether the nerves are compressed or the artery or veins are compressed.

Symptoms of arterial or venous compression from TOS are swelling in the arm, discoloration and/or temperature change in the hand, and a deep ache or pain in the neck, shoulder and/or arm. The arm may tire easily and feel heavy.

Symptoms of nerve compression from TOS include altered sensation in the arm (called parathesia), numbness and tingling in any area from the neck to the hand, muscle weakness and wasting (atrophy) in the arm, and sharp pain in the arm and hand.

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Pyschology Of Pain (8)

As with other chronic pain conditions, thoracic outlet syndrome can cause feelings of depression, sadness and loss. Often depression is heralded by other symptoms, such as increased fatigue, less energy, less interest in or enjoyment of activities, poor concentration, loss of appetite, worse sleep, and feelings of guilt or worthlessness. When these feelings or symptoms persist on a daily basis, the resulting depression may need to be treated with medications.

Frustration and anger also are normal responses to any chronic pain condition, including back and neck pain. However, because the mind can influence the body (and vise versa), such negative emotions can further aggravate pain.

References

(1) www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/thoracic/thoracic.htm#Organizations

(2) orthoinfo.aaos.org/fact/thr_report.cfm?Thread_ID=206

(3) www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/thoracicoutletsyndrome.html

(4) www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/thoracicoutletsyndrome.html

(5) www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/thoracic/thoracic.htm#Organizations

(6) www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/thoracicoutletsyndrome.html

(7) www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/thoracicoutletsyndrome.html

(8) www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/thoracicoutletsyndrome.html

Whiplash, Weekly Headaches Among Madeline’s Many Ailments

|

|

|

|

Madeline Jones is a 35-year-old woman working full-time as a receptionist and clerk for a law firm. She is in fair health and is slightly overweight. A mother of two children, ages 4 and 2, she enjoys playing golf, softball and walking but has not felt up to playing sports the last few years. Her chief complaint is the chronic pain in her neck and upper back, and particularly her right arm and hand.

Madeline’s Health History

Madeline Jones’ health history presents with the following:

- whiplash injury sustained in a motor vehicle accident in 1998;

- weekly headaches;

- right arm and hand pain with altered sensation;

- upper back, neck stiffness and pain;

- increased arm pain and weakness with lifting filing boxes to an overhead shelf.

What The Experts Say

On the following pages, Madeline’s problems are examined from the perspective of Massage Therapy, Physiotherapy, Acupuncture, Osteopathy, Chiropractic and Yoga Rehabilitation.

The Massage Therapy Approach

By David Zulak, MA, RMT

I strongly believe in not jumping to conclusions and avoiding, if possible, making assumptions ahead of the facts. I treat all diagnosis of musculoskeletal impairments or conditions that clients tell me they have received from others as subjective information, unless the condition is beyond my scope of practice.

|

|

|

|

The first step would be to clarify, during a case history interview, the relationship between the various elements reported by the client. Especially important is to place the occurrence of the whiplash within a timeline of the onset of her other symptoms. (However, a case study can only provide so much information.) Let us say for now that the whiplash preceded the other

symptoms and therefore may have been a major exacerbating event in regard to the other symptoms experienced by the client. We will assume that the symptoms listed in the case study are chronological.

During the process of meeting the client, doing the assessment and carrying out a treatment plan, observations will be made about the client’s posture and movement patterns. Asymmetry of structures and their restrictions in range of motion, and tissue texture changes in the cervical spine and upper extremity will all be noted.

All of this information, in turn, will be placed in the context of the client’s overall health and fitness. For example, postural asymmetries that may be noticed in the lower limbs or the lumbar spine and pelvis will be looked at as possibly providing the pre-conditions or “body-environment” within which the client’s trauma and/or the impact of their activities of daily living have expressed themselves in the specific manifestation as observed in the acuity or chronicity of their specific complaints and their unique collection of impairments.

Following is a short list of some of the specific things to check out during observations:

- the overall head position that Madeline Jones presents with;

- the lordosis of the cervical spine (excessive lordosis due to hypertonic and short extensors etc. of the neck; or an all too common post-whiplash “reversed curve” from a previously spasming longus colli which is now fibrotic and short). It is wise to compare this in turn with thoracic curves, (both kyphosis/ sagittal plane, and lateral curves through the coronal claim);

- the orientation of the shoulder (clavicle, scapula and positioning of the glenohumeral joint);

- how the affected arm is carried, (internally rotated for example);

- general tissue health in the affected upper limb (edema? hyper- or hypotonic musculature, condition of the skin, blood flow, venous drainage, etc. as compared to the other limb) – and, as mentioned above, what is the condition of the structure of the spine, pelvis and lower limbs and in what ways could they be participating in the client’s complaints and impairments?

- observation of the hand and forearm being pale, with coolness to the tissue of the hand and arm (when compared to the unaffected side) may suggest an arterial compression. A darker shade to the affected arm and hand can suggest venous return restrictions. (Usually the veins are engorged on the dorsum of the hand. Compare both hands carefully however, as recent physical exertion or being in a hot environment can cause this in both hands. The unilateral observation is suggestive here.)

The hand can also be cool with restricted venous return as it prevents proper perfusion of the tissues. Edema on the affected side (with no history of recent trauma) may indicate compression on the lymphatics. A referral back to their physician is

warranted, if they have not already discussed this with their MD.

Active Free Range of Motion (AF-ROM) testing will provide the information concerning the client’s ability to do specific movements. At this level we will observe basic impairments of movement.

In this case, we clearly need to observe both the cervical spine and the shoulder girdle. Since in this case, if we suspect TOS as a possible explanation for Madeline’s arm pain and weakness (and it is the topic to be written on!) we should rule out the cervical spine prior to testing for TOS specifically anyways, so let’s begin there. AF-ROM of the cervical will probably reveal a number of restrictions and possible discomfort in anatomical range of motions (each considered a cervical AF impairment) due to of the chronic nature of upper back and neck stiffness, and persistent headaches.

Careful recording and a good grasp of anatomy will give us a list of many tissues (associated with each impairment) to check out with other testing as we proceed. What will also be of interest is if AF of the neck provokes any symptoms in the arm.

Passive Relaxed movements (PR-ROM), which includes investigating the cervical spine with “joint play” (joint mobilizations such as translation through facet joints) will help us create a list of any impairments to motion found, that could be due to ligaments, joint capsules, etc. and to musculature that will not ‘let go.’

Appropriate overpressure at end-range of each anatomical range of motion (but not to be done in extension) will help to clarify if any non-contractile tissue is responsible for her symptoms, and may also provoke any neurological sources for the impairments reported in the arm.

This form of testing often reveals the sources of inter-segmental impairments in motion. These can often be matched with the more “gross” impairments seen in AF. At this point we can begin to list the structures and supportive tissues that we may need to address through Swedish massage, joint mobilizations (oscillations) and special techniques like Muscle Energy.

One important reason to be thorough here with PR is that we need to establish whether the client’s cervical spine has been left with any persistent segmental instability due to her whiplash. Two important reasons for establishing the presence of segmental instability are:

|

|

| David Zulak

|

1) That a clarification around this could explain a lot concerning the persistent hypertonicity and bouts of spasming muscle, which in turn could be activating Trigger Points (TrP);

2) Such instability can often compromise the nerve roots at that level. Finding such an impairment can alter our whole treatment approach as we now have to tread that fine line between reducing excessive hypertonicity and its accompanying restriction of motion (“stiffness”) while retaining for the client sufficient muscle splinting to protect the unstable segment(s). Treating to relieve pain will need to be accompanied by strengthening of the necessary musculature.

David Zulak, MA, RMT. David has been a massage therapist for more than 12 years, and has been teaching for 10 years, in private vocational schools, community colleges, and CEU courses for MTs. He is also a regular contributor to Massage Therapy CANADA magazine with his “Essentials of Assessment” column.

We certainly need to find the causes of Madeline’s headaches, in order to efficiently treat them. Often that treatment could be the result of helping regain appropriate muscle balance that will support the neck in an appropriate relationship with the other elements of the body upon which it sits, providing at the same time, pain free mobility.

As we move onto Active/isometric Resisted testing (AR) of the musculature of the neck, we can see the status of the involved musculature and what role it may be playing in her symptoms. Direct experiences of pain locally, or referred into other areas of the head, upper back or into the arm could be found to reproduce some or all of her collection of symptoms. We match the musculature that would be involved with the motions that provoked impairments like pain etc. and add that information to our list of tissues, as we map out the issues, to take into consideration, in developing a treatment plan specific to Madeline.

|

|

Cervical Rib Cervical Rib If the client tells us that they have a “cervical rib” we should find that palpable. The “rib” (or excessively long TVP) would have to be long enough to reach around forward enough to interfere with the neurovascular bundle when the client rotates to that side. If this was the case, and so is the cause of the TOS, we could still address the issues of tissue health in the arm and the hypertonicity and pain in the neck and shoulders (based on our findings above). The “rib” itself needs to be assessed by the appropriate medical professional. |

Many muscles in and around the cervical spine can refer down into the arms via Trigger Points (TrPs) and mimic TOS symptoms. If these show up in our testing and reproduce the client’s complaints, we then have the bulk of the information we need to compose a treatment plan. If we have not yet found the source(s) of the arm symptoms, then we must continue testing.

While testing the neck, a quick run through of the Compression Test, Distraction Test, Lower Quadrant/ Spurling’s Test and Valsalva’s Manoeuvre would shortly reveal if compression of nerve roots in the cervical spine are contributing to local pain, as well as pain in Madeline’s upper extremity. If we get positive results to our neurological testing then we refer the client back to their primary physician to follow up on those, as we continue with the treatment plan that we will arrive at. (once all testing is done). If we do not reproduce the symptoms in the arm then we have ruled out the cervical spine as their source.

Prior to TOS testing proper, we should investigate the shoulder through AF, PR with over-pressure, and AR testing. This quick run through of ROM testing would provide a comprehensive rule out of the shoulder’s involvement, particularly if we do not reproduce the symptoms in the arm and hand.

Note: While testing the cervical spine and shoulder, it would not be surprising to see several “positive results” such as pain or restrictions in motion, but many of these may not actually reproduce the chief complaint, which must remain our focus throughout this testing. They are, however, not to be ignored as they often point to the underlying or pre-existing conditions that may well have led to the chief complaints, or be the consequence (compensations) that are “effects” of the primary

complaints. For example, finding restrictions in the shoulder that, through testing, point to the impairment of clavicular function, will have a direct impact on understanding any positive tests that are found when testing for TOS specifically.

Depending on the exact path that the pain/symptoms travel in the arm, and the description of the nature and area of the altered sensations in the arm and hand, I would be tempted to rule out the elbow and wrist with AF motions followed with overpressure applied at end-range to quickly rule out those joints as sources.

Further, if the path or area of altered sensation and her experiences of muscular weakness pointed to specific peripheral nerves, I would also do the tests for those corresponding possible compression syndromes, such as radial tunnel syndrome, pronator teres syndrome, carpal tunnel tests such as Tinel’s signs and/or Phalen’s, to name a few.

If we now find the source of the client’s compression symptoms while performing these compression tests, then those tissues involved are incorporated into our treatment plan.

Assuming the symptoms in the arm and hand can not be sourced in the arm, forearm or hand then it is time to consider doing a comprehensive series of TOS test.

There are at least three areas that could be considered sites of compression, and we need to investigate each. It is wise to suspect that we could very well find that more than one area or set of structures is responsible for the symptoms experienced by the client. Sometimes the term “double crush” is used in this situation. Anatomically, it often makes sense that what would, for example be involved in an “anterior scalene syndrome” version of TOS, includes elements that could also contribute to a “costoclavicular syndrome.”

Order of Testing

|

|

|

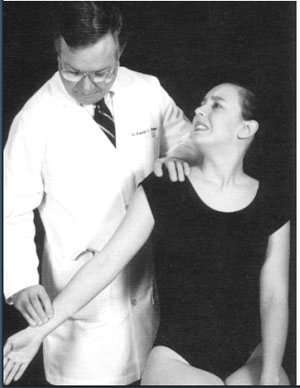

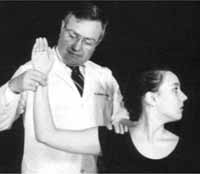

Anterior Scalene Syndrome

The usual ordering of the testing is to begin with structures at the neck and move laterally. So, our first test is often called Adson’s Manoeuvre, though a more appropriate name would be “Anterior Scalene Syndrome Test” as it refers to the name of the structure in the test, and when positive the syndrome is often named the “Anterior Scalene Syndrome.”

This test is designed to investigate for compression of the brachial plexus at the triangle formed by the anterior & medial scalenes and the first rib. The nerve roots C5 to T1 and the artery leading to the arm pass through this triangle. The artery and C7, C8 & T1 are the most susceptible to compression as they are at the lower anterior angle where compression takes place when the first rib is elevated and the scalenes are shortened or in spasm. Since C7, C8 & T1 are most at risk here, it is not surprising that the ulnar nerve in the hand is symptomatic in this syndrome.

If positive, we know to address the scalenes specifically along with other musculature that may hold the head and neck in a position that keeps the scalenes short (such as the SCM, all neck extensors, and musculature such as the pectoralis minor which helps to protract the shoulders, which positions muscles like the upper trapezius and levator scapulae in ways that

lead them to be hypertonic.)

I would like to make a comment about TOS Testing: The positive sign is often said to be the loss of the radial pulse at the wrist. To this I say “Yes & No.” Yes, when the symptoms being investigated are suspected to be blood flow impairment to the limb, which generally shows itself as parathesia in the whole hand.

However, to be truly positive for a nerve compression the pattern of such a compression needs to be reproduced by the test. We can generate so-called ‘positive tests’ by getting a loss or reduction in the pulse, but if we do not reproduce the client’s chief complaint, then we should not call the test positive.

If this test (or any of the TOS tests depicted here) is positive, then just prior to stopping the test (so, continuing to hold the arm in position and continuing to monitor the pulse) we would have the client lower their chin to chest. This chiropractic version of the test (Eden’s) helps to establish if the first rib is ‘stuck’ or being held in an elevated position.

|

|

|

During the classic versions of TOS testing the client is ask to keep the chin up and to take a deep breath: the anterior scalene test (either version) is meant to not only tighten the scalenes but also to lift the first (and second rib), all of which contribute to the syndrome. Therefore, the dropping of the chin to chest (as in “Eden’s) and the release of the breath (letting the client now breathe normally) should enable the first ribs to drop and so the pulse should return, or the symptoms lessen.

If these actions/repositioning do not cause the pulse to return, we would suspect the first rib is being held fixed in elevation. We can later palpate the first rib with musculature and other tissues slackened on the affected side and then palpate for motion in the first rib as the client breathes deeply. If restricted, then we will need to employ in our treatments joint mobilization techniques or Muscle Energy to restore motion to the rib.

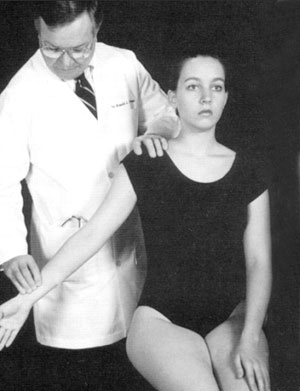

Costoclavicular Syndrome

The Costoclavicular Syndrome testing is next. As the name suggests, we are testing to see if this is an area where compression to the neurovascular bundle is occurring between the clavicle and ribs.

We know that a positive result need not rule out the Anterior Scalene Syndrome, as the scalenes are the principle culprit in holding the first two ribs elevated, which would narrow the space between the clavicle and the ribs. Hence, we could also find a positive here as well.

|

|

|

|

Further, the tissue here that would be added to the list to treat would be the subclavius and/or the pectoralis major both of which can contribute to depressing the clavicle.

Also, joint mobilization techniques applied to the sternoclavicular joint and the acromioclavicular joint would also be used. To do so, ensure that the joint structures themselves are mobile and mobilization of them by oscillations in turn reflexively relaxes the musculature attached to the clavicle. (Note that if the joints associated with the clavicle were restricted we would have noticed restrictions in shoulder range of motion.).

It is my experience that the anterior scalene syndrome and the costoclavicular syndrome are both involved, contributing to the compression in varying degrees. A positive test of either leads me to treat the totality of structures and tissues involved in both.

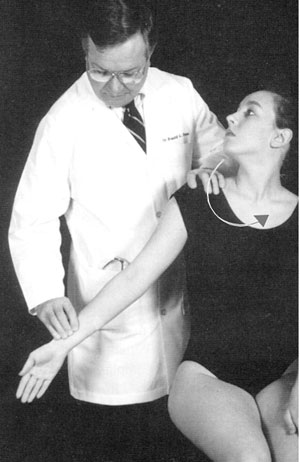

Pectoralis Minor Syndrome

We move along to test for pectoralis minor syndrome: where the neurovascular bundle passes between the tendon of this muscle and the ribcage.

|

|

ILLUSTRATIONS & PHOTOS: Evans, Robert, Illustrated Essentials in Orthopedic Physical Assessment, 2nd Edition, 2001 |

The classic test for this is “Wright’s Hyperabduction test” (see left). If positive we should follow up this test with palpating the upper ribs that would be involved and see if they could be contributing to this site of compression by being fixed in an inhaled position.

If so we need to address this rib dysfunction and stretch out the pectoralis minor. As the pectoralis muscle is one of the usual suspects in protracted shoulders (and Janda’s “upper cross syndrome”) we could find this postural condition here. If so, it would go a long way to explaining the whole set of symptoms Madeline has been experiencing, as the foreword head posture would account for tight erectors in the cervical spine, which in turn often generate headaches. The lifting of heavy boxes overhead could account for the Pectoralis Minor Syndrome symptom picture, and if Madeline has the forward head posture that can go with a shortened pectoralis minor, we can then develop an integrated and comprehensive treatment plan. Short-term or initial goals would include alleviating pain, sustaining tissue health and beginning the process of rebalancing the musculature of the neck and shoulders.

The First Step

The first step is stretching the short and tight musculature, which could be accomplished by a combination of muscle stripping, myofascial work, and post-isometric relaxation (PIR) stretching. The latter would move right into Muscle Energy techniques to mobilize restricted joints if present in the cervical spine.

This work would be assisted by giving the client stretching exercises for the pectoral muscles, and upper back and neck extensors of the cervical spine and head which the client should do between treatments.

Begin addressing overall postural issues – “balancing the pelvis.” We need to establish a level base for the spine upon which to rebalance the shoulder girdle, head and neck. Give stretching to hamstrings, quads, hip flexors, etc, as appropriate to start this process.

Second Step

Application of stimulating techniques to the anterior neck muscles and the lower trapezius should only begin after the short contracted muscles and tissues are well on their way to being restored to their normal length.

- We can use some AF chin tucks initially to act as concentric strengthening of the anterior neck muscles (to begin “waking them up to do their job”). The anterior neck muscles can then be progressively strengthened by more challenging exercises as the client is ready for them.

- Exercising and strengthening the lower trapezius also need to be done carefully as this retractor of the scapula is often very weak and easily injured.

Third Step/Longer-term goals

As the shoulder girdle and neck begin rebalancing the TOS usually begins to subside. If any muscle atrophy or de-conditioning has occurred in muscle in the arm, forearm or hand they should be addressed as soon as you feel that blood flow and neural innervation have normalized.

Prior to that (as an immediate or short term goal) massage and AF motion will suffice to sustain muscle function and assist in the restoration of tissue health.

Further Steps, if necessary

If symptoms in the arm and hand still persist, then upper limb tension tests (ULTT) could be employed to see if the chronicity of Madeline’s TOS has caused the neurovascular bundle to become enmeshed or constricted in the pectoral fascia.

I would run through the ULTT for the various peripheral nerves. With a positive test I would first refer the client to have the nerve tested for damage, and only when given the “all clear” would I then re-double my myofascial work in the pectoral area and use the ULTT to gently stretch the nerve within the tissue, ‘teasing’ it to release and regain its ability to slide within its pathway.

If I had not found a specific cause for Madeline’s symptoms, I would still be able to develop a treatment plan with her and address many of the impairments found (loss of range, pain, hypertonicity, tissue health, etc.) based on the impairments found in the assessment.

The short-term goals would centre on reduction of pain, maintaining tissue health and beginning improvements of range of motion.

Longer-terms goals would centreon restoration of posture and muscle balance. The hope, here, would be to alleviate most of Madeline’s cervical pain and headaches. Once a number of these impairments are resolved (which ever ones they may be) reassessment can often uncover the source(s) of the chief lesion since a number of “red herrings” have been removed from the picture.

Traditional Chinese Medicine … Acupuncture

|

|

|

|

Atraditional Chinese medicine assessment consists of four general classifications of examination: Looking; Listening and Smelling; Asking; and Touching. Information relevant to Madeline Jones’ case study is included within each classification.

Looking

- General appearance such as physical shape (overweight), posture, guarding

- Skin coloring or ulcerations on the skin

- Tongue diagnosis is an instrumental aspect of TCM, which is used in conjunction with other symptoms and signs

- Review of relevant diagnostics such as X-rays, MRI, nerve conduction testing and/or ultrasound

Listening and Smelling

- Voice and respiration

Asking Questions

- Present and medical history … Madeline’s chief complaint of chronic neck and upper back pain accompanied by right upper extremity altered sensation would be discussed in detail to understand the affected areas, the pathway of radiating symptoms and the nature of the pain. Any correlation with initial symptom onset, for example from the whiplash injury, is of clinical importance. The activities of daily living (ADL) and/or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), which are correlated with exacerbation in symptoms such as repetitive occupational tasks, occupational ergonomics, lifting of children should be modified

- Medication administration

- Current therapy

Touching

- Palpation over various body and acupuncture points;

- Pulse diagnosis is a sophisticated art and important aspect of TCM diagnosis. It is similar to tongue diagnosis as it is not absolute, but it is important in understanding the entire clinical picture. To effectively measure outcomes, additional objective measurement and testing is recommended.

For this case study, it should include the following:

- Neck, upper back and upper extremity palpation;

- Verbal/visual analogue scale(s)

- Cervical spine, thoracic spine, upper extremity range of motion (ROM)

- Upper extremity reflexes

- Upper extremity sensations

- Upper extremity and grip strength

- Right hand visual assessment of soft tissue conditioning, presence of ulcerations

- Right hand cutaneous temperature

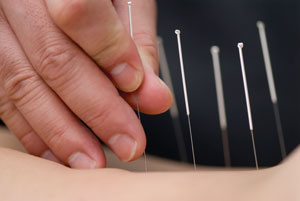

Description of primary modalities used

- Traditional Acupuncture

- Heat therapy without the presence of paresthesias.

Traditional Acupuncture is the insertion of fine gauge needles into the epidermis at specific acupoints to encourage the required physiological response. This primary treatment modality is based on two foundational theories: Eastern Theory and Western Theory. For theory explanation and clinical trial references, visit www.lisakervin.com

Short-term goals for this client, including method of treatment utilized to reach those goals

- Decrease pain in neck and upper back

- Decrease sensation in the right arm and hand

- Ergonomic analysis

Brief treatment plan

Frequency of acupuncture treatment recommended would depend on nature and description of pain, other concurrent therapies, and the activities correlated with exacerbation.

Long-term goals for this client, including method of treatment utilized to reach those goals

- Improve posture

- Increase strength (right upper extremity)

Information or comments about referral and/or a multi-disciplinary approach with other health care professional in the treatment of musculoskeletal injuries/conditions

A multi-disciplinary approach with other health care professionals in the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions or disorders is ideal. Depending on the case, a variety of clinicians may be helpful including a Doctor of Chinese Medicine/Doctor of Acupuncture, Registered Massage Therapist, Physical therapist, and Doctor of Chiropractic. However, it is critical to baseline implementation of all therapies in order to accurately depict an individual’s response. Optimal outcomes occur with treatment/modalities being performed by clinicians in their field of expertise.

|

||

| Lisa Kervin

|

Lisa Kervin, CMD, Dr. Ac, Acupuncture Specialist

Professional Highlights

- Extensive experience in clinical rehabilitation;

- Private practice at Lisa Kervin & Associates Inc. in London, Ontario, Canada;

- Assessor for Acupuncture medical/rehabilitation for St. Joseph’s Health Care London Designated Assessment Centre ;

- Active Member of Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture Association of Canada (CMAAC) and Professional Acupuncture Association of Ontario (PAAO)

Education & Training

- Certification, The Institute of Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture of Canada;

- Attained the highest 4-year graduate level education in Acupuncture available in Canada;

- Specialization in TCM Acupuncture for the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders;

- Degree, Continuing BHSc, University of Western Ontario

Therapeutic Yoga Practice for TOS

By Cathy Ryan, RMT

Ultimately, the aim of Yoga therapy is to teach the brain and body to work in harmony

As a fascial practitioner, one of the most exciting aspects of my own Yoga exploration has been the awakening of a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the fascial lines and the asanas or postures. This has greatly influenced my work and expanded my awareness of the value of Yoga as a therapeutic modality.

Although it is a relatively new “mainstream” concept here in North America, the use of Yoga as a form of therapy is as ancient as the discipline itself. Yoga Therapy in its traditional application (Cikitsa) exemplifies the very essence of holism and an organism’s innate propensity to heal. In his book, Yoga for Wellness, renowned Viniyoga teacher Gary Kraftsow says, “The basic principle of Yoga Cikitsa is that diseases are symptoms of imbalance; and therefore, the orientation of Yoga Cikitsa is to restore balance.”

Imbalance in structural alignment is one piece of that pie. To quote Ida P. Rolf, “structure determines function.” This speaks to how our shape or form will impact our physiological functioning and how tuning/balancing of the myofascial system effects the functioning of the entire being. That having been said, bear in mind, that Yoga embodies much more than just the structural element of “being.”

Refer to the Fall 2007 issue of Massage Therapy Canada magazine for a more comprehensive look at Yoga and some of its therapeutic possibilities.

Many thanks to my Iyengar Yoga teacher, Karen Major, for her contribution and time. Karen selected the asanas shown, sequenced this practice and provided the asana descriptions below.

As you can see, some of these asanas are quite demanding. It is imperative that you work with a knowledgeable teacher who can safely guide you.

Much like the principles of Massage Therapy, with Yoga Therapy, correct assessment, selection and sequencing of the asanas are paramount to the therapeutic outcome. Specific asanas are mindfully chosen and sequenced to not only achieve a desired result but must also be appropriate for the individual’s condition, state of health and level of practice. This sequence, based on the teachings of BKS Iyengar, also shows how props can be utilized to help make the asanas more available and productive.

I figured that I would be a reasonably good candidate for this photo shoot as the tightness through my chest, shoulders and arms would help accentuate the value of the asanas selected.

Not only did I benefit from the practice, since it targeted some of my issues, I also had the privilege of a one-on-one session with Karen. Hey … this writing gig is a tough job but someone has to do it!

All of the Yoga asanas (postures) selected/shown are to help relieve compression and the symptoms associated with TOS, by opening the chest and creating more mobility in the thoracic and cervical spine as well as the shoulder joints.

|

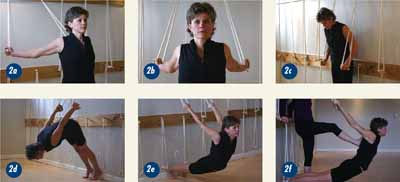

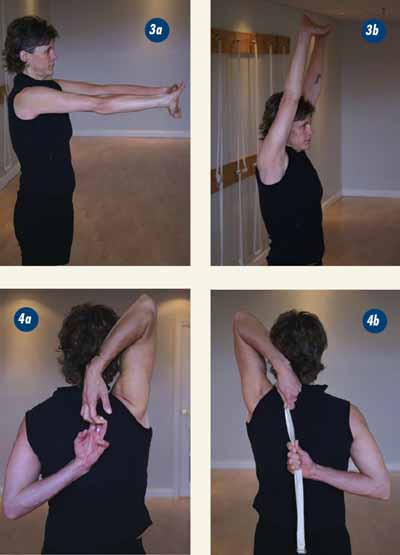

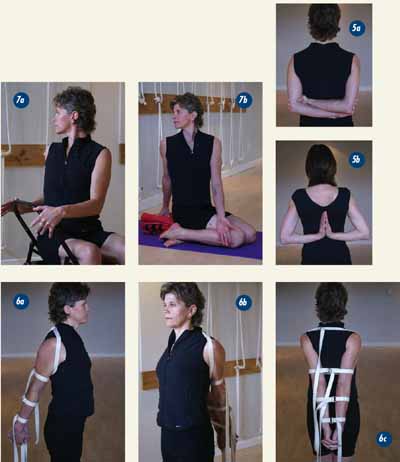

| Block Savasana (Fig. 1a, b) helps to create an awareness and opening in the mid thoracic as well as increasing the mobility of the shoulder. The Rope Series shown (Fig. 2a, b, c, d, e, f) is to create a stretch for the pectoralis muscles as well to encourage movement from the back spine (further assisted by placement of the teacher’s foot in the thoracic region). 3, 4 and 5 all help to mobilize the shoulders in several ranges along with wrist extension/shoulder rotation. In these next three the tightness through my chest, shoulders and arms is quite evident. Parvatanasana (Fig, 3a, b), in 3b you can see the difficulty I have with getting my wrists, elbows, ears and shoulders to line up … I am a bit off the plumb line here! Gomukasana (Fig. 4a, b: modified), I needed some belt-assistance on this one. |

|

|

| Namaskar/hands behind the back (Fig. 5a modified, 5b: classical pose), Karen pitched in for the classical pose/5b … my tight shoulders are still in the “modified” stage/5a. The Belt Work, (6a, 6b, 6c) provides an understanding of the shoulder movement and corresponding shoulder blade action to support an open chest. Twists, like Bharadvjasana (7a, 7b) and Utthita Marichyasana (9a) are key to mobilizing the thoracic chest and help with improving range of motion of the cervical spine. |

|

| Urdhva Dhanurasana (8a: modified with blocks and knees bent, b) is an intermediate level asana which assists with mobilizing the spine and shoulders and opening the front chest. In 8b my hands turn outward due to the tightness (chest, shoulders and arms). Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (10a) assists with mobilizing the thoracic spine and opening the front chest in a supportive way. Salamba Sarvangasana (11a) … shoulder stand … aaahhhhh, I love this one. Good for the mind, body and soul! … Namaste |

|

An Osteopath’s Approach

By Brad McCutcheon, Dip (SIM), Dip (MT), RMT, SMT(C), D.O. (MP)

Having read the submissions from my physiotherapy and chiropractic colleagues, I found it an interesting task to submit a synthesis of how an osteopath treats a condition while not being able to really assess and find out what is actually wrong with this patient. With this in mind, the following is a general overview of how an osteopath would approach and discuss the treatment of Madeline Jones as if she presented to one of our clinics.

|

|

|

|

An osteopath approaches a patient in a holistic sense, every time without exception. Meaning, when a patient such as Madeline undergoes a whiplash injury they are traveling at a certain velocity, under the constraints of a seat belt, a whiplash can injure many tissues all which will need to be assessed and notes taken.

To keep the list short, let’s assume that Madeline was wearing a seatbelt and that she was the driver of the car in her whiplash. This is an important piece of information due to the fact that a seatbelt is a fixed structure around which the motion of the patient continues during the accident.

If the seatbelt is worn on left shoulder such as with the driver position then, the right side of the body rotates around this fixed structure and causes force trauma to be embedded in the bones, ligaments and fascias of her body. As a sidebar, a passenger in the same accident would have the force trauma on the left side going forward around a right fixed structure.

In our assessment, a thorough history would be taken to include the pain, and all the pertinent pain questions, her MVA and all questions including those about the mechanism of the accident and what her body did during the accident. We ask questions about all the systems of the body to see if she is experiencing visceral symptoms along with her more obvious somatic symptoms.

These visceral symptoms are common after an MVA due to potential injury to the Vagus nerve as it courses down the neck into the chest, and these visceral symptoms often get missed by many other health practitioners at the hospital.

Due to the nature of the chronicity of the pain that Madeline is continuing to experience, we would assume that this was not solely an issue of somatic dysfunction, or that whatever Madeline has done for her dysfunction has been limited in its efficacy.

Osteopaths are great believers in the orthopaedic model as a system to allow for safety and to rule out any major problems that might be interfering with the patient’s ability to heal themselves. A complete postural, range of motion and neurological testing including in this case, dermatomes, myotomes, reflexes and temperature testing would be performed. Afterwards special testing such as Elvey’s (ULTT), compression testing of the C-spine and quadrant testing of the C-spine, brachial plexus testing, Adson’s manoeuvre, and pulse testing for circulatory compromise (Reid, 1992, Pollak, 1986).

These tests are routine and notes would be taken. At this time, if there were no reasons for concern or

referral of Madeline to a neurologist or back to her MD for further testing, then we would proceed to our osteopathic assessment.

To an osteopath, the patient is a functional unit, a complete package that has been through a whiplash. In the past her cranium has been forced forward through the same forces that the neck and shoulder have been even though, while currently the symptoms appear to be of TOS in nature (and that is the realm of this discussion). Madeline’s headaches might be coming from any number of different sources (Sanders and Haug, 1991). We would evaluate the state of that which we call her “vitality” (the movement of CSF in her ventricles of her cranium and its influence on the tissues of the spinal cord) and see if it is adequate. We would move the joints of her C-spine through mobility testing to determine if there is a presence of any somatic dysfunction (the vertebral bodies’ tissues causing pain or functional problems). These could either be group dysfunctions or segmental dysfunctions.

To continue our assessment, the thoracic spine would be assessed for somatic dysfunction as would be the lumbar spine, pelvis and lower extremities. All of these structures are assessed because, as a patient with a TOS dysfunction, Madeline brings to my office many histories and experiences other than just her MVA and her TOS; and it is possible that a dysfunction of her right SI joint is causing her to change her gait in a manner that is causing a sidebending of her lumbar spine, a slight scoliotic pattern in her thoracic spine and a compression of one side of her neck leading to the somatic signs and symptoms that she has presented with.

The final item to most osteopaths although the order here is not as important to some, is to test her lungs and their ligament attachments, as well as her pericardial ligaments, because they attach to the cervical spine. So, too, her esophagus and its ligamenteous attachments, the position of her mesentery, liver, and pancreas, and possibly her large intestine.

Some of these organs have direct attachment to the cervical spine (Netter, 2005, Gray and Leonard, 2005, Moore and Dalley, 1999) and are therefore influencing the position and function of the bones and muscles that compose the cervical structure. In turn these visceral and deep structures also impact on biomechanical regions below the cervical spine and therefore their influence on body posture and movement affect the biomechanics of the C-spine as well. All of this is taken into consideration by an osteopath – and may or may not support the findings that were discovered in the earlier testing by other health professionals.

For me, this thorough assessment is what brings me success in my clinic. There is not a week that goes by that does not bring a pleasant surprise in my assessment, where something I uncover turns out to be the key to the successful treatment for that patient.

I was asked to discuss TOS and, while it is impossible to summarize goals and treatments from this list of possible findings, I will try to discuss the most common types of findings that cause the list of symptoms that Madeline appeared with.

Modalities Used:

Osteopaths (outside of the U.S.A.) are trained as manual therapists, so modalities are limited to that approach. They may have other backgrounds that they bring to their practice but Osteopathy is primarily a manual form of medicine. So all osteopathic treatment discussed here is done with the human hand. Osteopathic physicians, however, (trained in the U.S.A.) may have another set of modalities they would employ.

Short-Term Goals/Long-Term Goals

This is another area that is difficult to answer, both are the same: return the patient to normal function. One of the strongholds of osteopathy is that motion is life, without motion there is no life.

Our goals are always to get tissues that are not moving to move, once they are moving then we assure that fluids are entering and returning from the tissues and that the patient can accept these changes into their entire body. So in a way our short-term and long-term goals are identical.

Given the obvious exception of an acute condition where the short-term goals are to protect and make sure no further damage occurs to the injured tissue. With Madeline’s chronic problem, the goal would not differ much.

Treatment Plan

TOS has some common characteristics. The first rib, and Osteopaths will add the second rib, are quite often high or what we call superior. If they are low then the circulatory condition would worsen in the upper extremity.

The Cervico-thoracic junction is quite often compacted (stuck together and immobile), the scalenes shortened on the affected side. The pleural dome which attaches on the same vertebrae as the scalenes quite often shortened, there is accommodation in the upper cervicals (side-bending and rotation) due to the need to keep the eyes horizontal (Moore and Dalley, 1999, Gray and Leonard, 2005).

The clavicle quite often goes into external rotation, although I have often seen it compressed and with the subclavius quite shortened in an attempt to limit the pull on the nerve supply. The girdle is often protracted and the subscapular muscles are shortened. We would treat the interosseous membrane in the affected arm to relieve any tensions on the neurovascular bundle as it passes through it.

We would treat the biceps and triceps relationship as the neurovascular bundle passes between them in the brachial and axillary regions.

The pectoralis minor muscle and pectoralis major muscles often have adhesions to the ribs and in the case of minor to the vascularity itself, thus preventing normal flow of blood into and out of the axilla. The lymphatics would be looked at to determine if there is any problem with normal drainage from the upper extremity, or of more importance in this case, drainage into the thoracic inlet itself.

The cranium would have to be addressed to check for proper motion of the base bones and to assure that CSF was being delivered to the tissues of the spinal cord and therefore also to the local nerve roots which are usually affected with TOS.

Treatment of the sacrum would be accomplished in the first visit to assure a good base of biomechanical support for the patient. Even slight restrictions of the pelvis and ilia will create fascial distortions that could affect the shoulder girdle by way of the thoraco-lumbar fascias, latissimus dorsi and what osteopaths refer to as fascial chains, (tissues that are formed embryologically from the same tissues that even later in life are still related to one another and carry similar tensions within them biomechanically).

References

- GRAY, H. & LEONARD, C. H. (2005) The concise Gray’s anatomy, New York, Cosimo Classics.

- MOORE, K. L. & DALLEY, A. F. (1999) Clinically oriented anatomy, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- NETTER, F. (2005) Netter’s atlas of the human body, Hauppauge, NY, Barrons Educational Series, Inc.

- POLLAK, E. W. (1986) Thoracic outlet syndrome: diagnosis and treatment, Mount Kisco, N.Y., Futura Pub. Co.

- REID, D. C. (1992) Sports injury assessment and rehabilitation, New York, Churchill Livingstone.

- SANDERS, R. J. & HAUG, C. E. (1991) Thoracic outlet syndrome : a common sequela of neck injuries, Philadelphia, Pa., Lippincott.

|

|

| Brad McCutcheon

|

Brad McCutcheon is a member of the College of Massage Therapists of Ontario, the Ontario Massage Therapist Association, a certified Member of the Canadian Sports Massage Therapists Association, Vice President of the Ontario Osteopaths Association, and Director of admissions and pre-admissions for the Canadian College of Osteopathy in Toronto, Halifax, and Vancouver. He is a faculty member of the Canadian College of Osteopathy and the Wellington College of Remedial Massage Therapists in Winnipeg and the Western College of Remedial Massage Therapies in Regina. Brad is the owner of a private practice in Coldwater, Ontario and an educational consulting business.

Physiotherapy Perspective

By Deanna Huggett

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) may combine neurological and vascular signs and symptoms, however the signs and symptoms of neurological deficit, arterial flow restriction, or venous flow restriction may also be seen individually. As such, the diagnosis of TOS is typically one of exclusion.

There are several sites, between the base of the neck and the armpit (axilla) where compression of the neurovascular bundle can occur.

The causes of compression can be anatomical/structural (congenital or acquired) and/or functional.

Anatomical causes of TOS can be bony (osseus) in nature or soft tissue related. Functional causes typically involve muscle imbalances and may include postural alterations, psychosocial involvement, or respiratory alterations.1,2

|

|

| Physical modalities such as moist heat, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and ultrasound can be used to reduce pain and promote muscle relaxation.

|

Assessment:

The physiotherapy assessment begins the moment I first see Madeline Jones. Even before saying hello, I observe her overall posture, how much pain she appears to be in, the ease or protectiveness of her movements (i.e. walking, shaking hands, moving from sitting to standing and initial sitting posture), and her general demeanor (i.e. mood, tension, anxiety level).

The initial question-and-answer period provides insight into Madeline’s general health, current symptoms, aggravating and easing activities and past medical history. We also discuss her goals for treatment, and try to make these both specific and functional.

During her physical examination, I more carefully observe Madeline’s posture, particularly that of her neck and shoulder girdle. Both actively and passively, I assess her range of motion in her neck, thoracic spine, shoulder girdle, elbows and wrists. I assess her upper extremity nerve conduction by examining her reflexes, muscle strength and sensation.

A thorough strength examination of Madeline’s neck, shoulder girdle and upper extremity musculature, including grip strength, is necessary to determine any areas of weakness.

Palpation will reveal areas of tenderness in muscles, or along nerves. In TOS, it is typical to find restricted movement of the upper cervical spine and malfunction of the first rib. A restriction of this movement may be caused by tension in the scalene muscles, particularly the middle scalene.

Typical postural observations include a forward head position, rounded shoulders with shortening

of the small pectoral, upper portion of the trapezius, levator scapulae and sternocleidomastoid muscles.

In contrast to these areas of tightness, it is common to see weakness in the serratus anterior and lower trapezius muscles that stabilize the scapula.

The Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion Test, when positive, can indicate a malfunction of the first rib, a possible cause or contributing factor in Thoracic Outlet Syndrome.3

In Madeline’s case, to assess her right side, I passively rotate her neck to the left as far as possible and then gently bend her right ear towards her chest. If there is no forward bending movement, or if the available range of movement is less than half of that on Madeline’s left side, the test is considered positive.

A positive Tinel’s Sign (tingling in the distribution of the nerve) is indicative of possible compression of the nerve somewhere along its course. Tinel’s test involves tapping over the nerve and can be assessed over the different trunks of the brachial plexus in the neck and shoulder, medially at the elbow to assess the ulnar nerve and at the wrist over the carpal tunnel to assess the median nerve.4

Provocation tests attempt to reproduce the mechanisms involved in provoking the client’s symptoms, and a variety of provocation tests exist in the literature for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome.5, 6 However, most of these tests are considered unreliable, with positive test findings common in the normal population.

The most commonly used test is the Roos Test, which constricts the costoclavicular space and demonstrates the functional ability of the upper extremities. To perform the Roos Test, I ask Madeline to put her arms in the “stick-up” position (arms raised to the sides 90 degrees, elbows bent 90 degrees, with hands rotating upwards and palms forward).

In this position, I ask Madeline to repeatedly open and close her fists for three minutes to see if her symptoms (right arm and hand pain with altered sensation) are reproduced. The physical examination must be carried out with extreme caution so as not to exacerbate her symptoms.

Primary Modalities Used:

Physical modalities such as moist heat, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and ultrasound can be used to reduce pain and promote muscle relaxation.

In some instances, taping can be used to help elevate the scapular girdle and reduce pressure on the site of compression. Passive mobilization of the joints of the neck and upper thorax can help restore normal

movement in these joints, and general traction of the neck can also help to reduce pain. Painful exercises may need to be avoided initially because they may aggravate Madeline’s symptoms. However, it is important that passive procedures not be a substitute for active exercises and the correction of posture and muscle imbalances. Active exercises should be introduced into Madeline’s program as soon as possible.

Short-Term Goals:

A number of short-term goals are made to help decrease Madeline’s symptoms and improve her general mobility and function. The treatment for one goal will also work towards each of the other goals.

An active treatment strategy consisting of education, correction of posture and positions at home, at work and at night, daily home exercises, simulation of daily living activities, breathing exercises, and general aerobic conditioning will all be included in Madeline’s therapy program.

Madeline must be taught and encouraged to carry out a daily home exercise program and to change bad habits. She will report decreased pain and stiffness and decreased frequency and intensity of her headaches.

In addition to the modalities and passive treatments described above, teaching Madeline correct diaphragmatic breathing can help with pain management and improved mobility of the ribs.

Active mobilization of the upper parts of the neck can provide gentle stretching of muscles that are commonly tight and produce pain and headaches.

Madeline will demonstrate improved postural awareness.

She will be educated regarding deficits in her posture and taught postural control exercises for the spine, such as chin retraction exercises.

Correction of Madeline’s muscle imbalances will be initiated.

Strengthening exercises for the anterior serratus and lower trapezius muscles will be taught to improve the stability of the shoulder blade.

Stretching exercises will be provided for the upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, levator scapulae, scalene, and minor pectoral muscles (muscles that produce tension in the neck and shoulders, round the shoulders forward and produce a forward head position).

Activation and strengthening exercises for the scalene muscles will help to restore normal movement and function of the first ribs and upper thorax.

Shoulder exercises are included to restore the movement of the whole shoulder girdle and provide more space for the neurovascular structures.

Environmental factors contributing to Madeline’s ongoing symptoms will be corrected.

An ergonomic assessment of Madeline’s workplace will be conducted and recommendations provided for improvement.

Education regarding positions and postures, and how to integrate them into daily living activities (e.g. how to minimize Madeline’s discomfort while playing with her children and preparing meals)

Madeline will be able to complete her home exercises independently (correct technique without external cuing).

Regular review of exercises and instructions.

Treatment Plan:

The frequency of Madeline’s physiotherapy treatment sessions depends on the severity of her day-to-day symptoms and her ability to independently and correctly work through her prescribed home exercise program.

Initially, she would have treatments one to two times per week. After three to four weeks, her treatment sessions would be decreased to one to two sessions per month. It is important to gradually decrease the frequency of her therapy sessions to contain costs and facilitate her independent learning for self-directed care. One to two long-term follow-up sessions are advised to review and progress Madeline’s home exercise program.

Long-Term Goals:

Relapses in TOS symptoms are common and Madeline will likely need to continue with some level of exercising for an extended period of time. This is important not only from an injury management perspective, but also from a general health perspective.

As well, Madeline’s job is sedentary in nature, making a regular stretching and postural awareness program that much more important. A self-treatment program is imperative. Long-term goals for Madeline include:

- Madeline will be knowledgeable regarding the importance of participation in a regular exercise routine that includes site-specific exercises for her condition and general aerobic and strengthening exercises.

- Instruction in how to initiate and progress a general fitness routine.

- Madeline will be able to complete her exercise routine independently, and be able to successfully manage relapses in her symptoms.

- Education regarding how Madeline can self-modify her exercise routine if her symptoms return.

- Madeline’s participation in activities such as golf, softball and walking will not be limited by her current symptoms.

- Gradual reintroduction of sporting activities with education regarding pacing and biomechanics education (e.g. golf swing, softball throw).

Other:

Clients typically have improved outcomes when a multi-disciplinary team is involved in their care. Each health profession provides a unique set of skills and perspective on how to maximize the client’s abilities and reduce pain and dysfunction in an efficient manner.

Ideally, Madeline has seen her family physician prior to initiating her physiotherapy treatment for radiographic (x-ray) and possibly neurophysiological examinations (e.g. EMG) to rule out other causes for her symptoms (e.g. cervical disc herniation, cervical spondylosis, polyneuropathy).

Massage therapists, chiropractors, acupuncturists and physiotherapists act symbiotically to address the pain, muscle imbalances and asymmetries, postural dysfunction and functional impairments associated with TOS and other musculoskeletal injuries/conditions.

It may also be appropriate to involve a social worker, psychologist and/or psychiatrist to address any psychosocial issues surrounding Madeline’s case.

References

- Vanti C, Natalini L, Romeo A, Tosarelli D, Pillastrini P. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome. A review of the literature. Europa Medicophysica. Vol 42, 2006 Sep 24.

- Lindgren K-A. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome: a 2-year follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:373-8.

- Lindgren K-A, Leino E, Manninen H. Cervical rotation lateral flexion test in brachialgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992;73:735-7.

- Magee D. Orthopaedic Physical Assessment, 3rd edition. 1997. W.B. Saunders Company.

- Gillard J, Pérez-Cousin M, Hachulla E, Rémy J, Hurtevent JF, Vinckier L et al. Diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome: contribution of provocative tests, ultrasonography, electrophysiology, and helica computed tomography in 48 patients. Joint Bone Spine 2001;68:416-24.

- Rayan GM. Thoracic outlet syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1998;7:440-51.

|

|

| Deanna Huggett

|

Deanna Huggett is a physiotherapist with a Master of Science degree. She has been practicing for seven years and currently manages her own consulting company, The Travelling Physio, in London Ontario. An avid runner and triathlete, she has completed two Ironman competitions. You can contact Deanna at www.thetravellingphysio.com.

Chiropractic Approach

by Dr. David Anderson BSc (HK), DC, FCCSS(C)

Assuming Madeline Jones was a new patient to our clinic, a thorough history and physical examination would be mandated. The diagnosis of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) is a clinical one. Other neurological or vascular conditions can be ruled out with diagnostic procedures.

|

|

|

|

Cervicogenic shoulder/arm pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, adhesive capsulitis, acromio-clavicular or

gleno-humeral joint sprains, cervical /upper thoracic facet syndromes, degenerative or herniated disc

disease in the cervical spine and osteoarthritis are some of the more obvious considerations to look for and rule out during examination.

Direct neuropathies indicating conditions like carpal tunnel, ulnar nerve compression or motor neuron disease can be ruled out through nerve conduction studies. Generally, TOS does not elicit abnormal nerve conduction even with symptoms as described above. In any event, it is rare for the typical chiropractic clinic to have ready access to electromyography, arteriography and/or diagnostic imaging beyond standard x-rays.

Once a suspicion of TOS has been established, a diagnosis to identify the causative mechanism is imperative so that appropriate treatment is effective and timely.

Specifically, TOS has been characterized by signs and symptoms resulting from compression of the subclavian artery (or more rarely, the subclavian vein) and the related brachial plexus.

In chiropractic, TOS is often categorized based on the location of anatomical compression on the neurovascular bundle.

There are a number of factors operating in four distinct anatomical locations, resulting in four distinct syndromes. These factors include: tight or hypertrophied muscles, ligaments, fibromuscular bands, or bony abnormalities in the thoracic outlet area. These rigid osseous boundaries, strong muscles, and fascial structures are common sources for syndromes of impingement or compression. Clinical testing can aid in identifying the offending anatomical structures responsible for applying pressure to the neurovascular bundle.

Origins of this condition include scalenus anticus, costoclavicular, cervical rib or pectoralis syndromes. This region is bordered by the anterior middle scalene muscles, clavicle, and first and second ribs. Within this area, the brachial plexus exits the cervical spine and passes between the anterior and middle scalene musculature, and under the clavicle and pectoralis minor muscle, along with the subclavian artery and vein.

TOS is characterized by pain, numbness, tingling, and/or weakness in the arm and hand due to compression against the brachial nerves and subclavian vessels as they traverse the course from the cervical nerve roots to the axilla through the thoracic outlet and cervicoaxillary canal.

The experienced chiropractor will identify the primary causative tissue abnormalities and address his or her treatment plan toward alleviating the symptoms through various manipulative techniques to both the soft tissues and joint complexes involved.

In the case where scalenus anticus is involved, soft tissue manipulations to improve the length of the muscle and reduce hypertonicty along with manipulation of the first rib and cervical facet joints dramatically improves the patient’s clinical presentation.

Generally, joint manipulation to the first and second costo-vertebral joints, sternoclavicular joints and the appropriate cervical and upper thoracic facet joints are safe and effective therapeutic approaches to this condition.

Specifically, cervical spinal adjustments to the contralateral side of scalene muscular tension should be considered as the vertebrae are rotated posteriorly on that side.

On the same side of scalene hypertonicity a seated (patient) technique can be applied where the chiropractor cradles the patient’s head (practitioner stands in front of patient) with his/her support hand and contact is made on the anterolateral portion of the vertebral body to be adjusted with the hypothenar region of the adjusting hand. The patient’s neck is laterally flexed to the uninvolved side and rotated towards the involved side. The adjustment is directed anterior to posterior and in an arc towards the contralateral side.

Increased range of motion and decreased symptomatology typically result. Repeat treatments may be required particularly when the condition has been longstanding.

It has been my experience that a therapeutic plan of 4-6 treatments over the first 2-3 weeks followed by fewer additional treatments spread over a following 3-4 weeks is sufficient in the majority of cases to see a successful result.

The chiropractor with a sports injury or active rehabilitation background will apply specific exercises to the region to improve shoulder neck and arm alignment particularly to prevent shoulder drooping and increased range of motion in all planes in the cervical spine and shoulder joint.

When the costoclavicular mechanism is the cause, relief from downward pressure on the shoulder is imperative. This can be attained through exercise and padding to reduce pressure on the shoulder as might occur from straps of any kind (brassieres, postal carriers etc.)

Myofascial techniques, ultrasound and electrical stimulation to involved soft tissues provides therapeutic value as well. Conservative therapy as described here has shown to be effective in the vast majority of cases (90 per cent).

• References available upon request

|

|

| David Anderson

|

David Anderson is a practising chiropractor in Newmarket, Ontario with a Fellowship in Sports Injury Management. He established his clinic in 1986 and taught at the Canadian College of Massage and Hydrotherapy for seven years. He runs a clinic that offers chiropractic, massage therapy, chiropody and homeopathy. Emphasis at the clinic is on the correction of musculoskeletal biomechanics and the rehabilitation of injuries from sport, work or auto accidents.

Print this page