Features

Education

Leadership

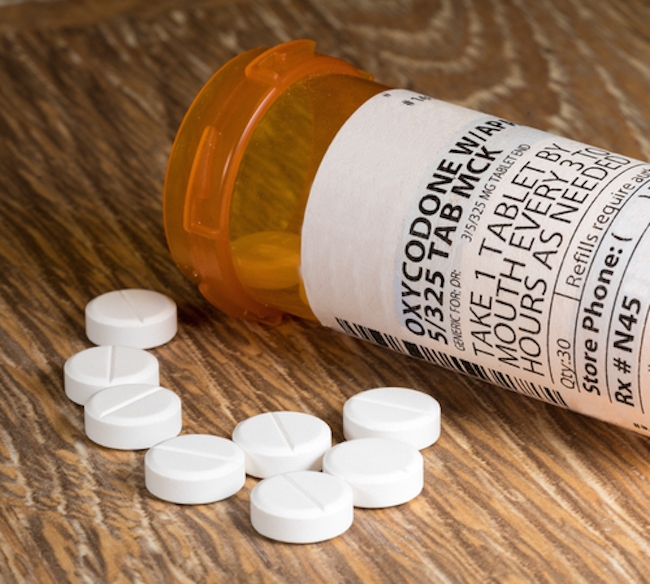

Chronic pain and the opioid crisis

Canada's unresolved pain problems have contributed to the growing opioid crisis that continues to result in thousands of deaths across the country. One in five Canadians suffer from chronic pain.

April 11, 2017 By Mari-Len De

Many in the health care community agree when it comes to effective and sustainable chronic pain management, there is no one magic pill or one treatment to rule them all. Chronic pain is a complicated beast that needs multilevel and multimodal approach involving teams of professionals of different skillsets and expertise.

The latest evidence of this need for a cocktail of measures comes from a recent clinical guideline issued by the American College of Physicians (ACP) on the management and treatment of acute, subacute and chronic low-back pain. In the document, the ACP enumerates a number of conservative approaches – spinal manipulation, exercise, yoga, massage therapy, low-level laser therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, among other things – as first-line therapy for managing low-back pain.

“(Health care practitioners) all play a piece in the puzzle,” says Dr. Stephen Burnie, a Toronto-based chiropractor who has done multiple research on the management and treatment of neck pain. “It’s important that chiropractors become more recognized for that large piece that we can fill in solving the puzzle, but we also have to be cognizant of the fact that as chiropractors we don’t have the whole answer.”

It’s been proven time and again that when chiropractors are integrated in primary health care, especially in the management of acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain, the outcomes are much better for the patients.

Ontario is seen as leading the charge in changing the face of the health-care system, one program at a time, toward an interdisciplinary, patient-centred approach. St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto is considered a pioneer in this area, where chiropractic has been successfully integrated in its primary care setting. The Ontario Primary Care Low-Back Pain (PCLBP) pilot project, for the last two years, has seen the pilot sites reporting better outcomes for patients.

Ninety-percent of patients seen at the Windsor-Essex PCLBP pilot site are chronic low-back pain patients, according to Dr. Dean Tapak, one of the chiropractors involved in the project. Patients are reporting significant reduction in their pain levels over the course of their respective treatment plans – many of them saying they have since either reduced or completely stopped taking their pain medications.

“We learned that patients, when placed in multidisciplinary settings – where you have specialists in different areas all coming together, sharing patient files, discussing patient’s management – it’s just that much better for the patient’s overall health and well-being,” Tapak says.

Multilevel approach

There are other factors beyond spinal manipulation and chiropractic care, however, that should be considered when managing chronic pain patients.

“Chronic pain is a multifactorial problem,” Burnie explains. “There may be organic problems – muscles, nerves, joints. There’s also other factors (like) societal issues.” People can have different responses to pain, and tolerance levels may vary. There are also psychological issues that must be considered when assessing pain patients.

Effective pain management must involve a biopsychosocial approach to assessment and treatment. When a patient is in pain, the health-care provider does not only look at the physical or peripheral areas of dysfunction, but also assesses the psychological factors, especially if the patient is exhibiting symptoms of depression, anxiety or stress.

Looking for signs of central sensitization is one way to assess for any psychological risk factors. When a patient cries out in pain even from the slightest palpation from a chiropractor, that’s usually a sign of central sensitization, notes Dr. Chris Carter, a chiropractor from Kelowna, B.C. Carter has a particular interest in pain management and has taken a master of science in pain management at the University of Sydney Medical School in Australia.

“We have to assess – are there issues going on in the brain that are amplifying the person’s pain experience?” Carter says, a CMCC graduate who spent 10 years in private practice in Perth, Australia, before moving back to B.C., over a year ago. Research has shown that when central sensitization occurs and patients transition from acute to low-back pain, the risk for underlying depression, anxiety or stress is higher.

Research has also revealed that for patients who have pre-existing depression and/or anxiety and then develop acute low-back pain, their condition is more likely to evolve into chronic pain, Carter notes.

Detecting high levels of affective disorders – stress, depression or anxiety – in patients with acute or chronic pain upon assessment should prompt chiropractors to make a referral to the family doctor for further psychosocial screening.

“Patients that are in the mild or moderate category of pain intensity or disability… they can be given conservative care, but you’re (also) monitoring for any psychosocial risk factors or maladaptive cognition that you discovered in your examination,” Carter suggests. Maldaptive cognition includes fear avoidance and “catastrophization,” where people tend to overanalyze their pain and always think about the worst-case scenario.

Minding the psychosocial aspect is crucial to effective pain management. When patients talk about their pain with their health-care provider and they’re tearful, seemingly frustrated, overwhelmed or having suicidal thoughts, that’s a red flag that a mental health specialist should be brought into the care protocol, says Karen Overholt, a social worker at Essex County Nurse Practitioner-led Clinic.

In her line of work, Overholt sees a “strong connection” between chronic pain and mental health.

“If we’re not feeling well on a daily basis, we start to deal with negative thinking. Some of the main facets of depression and anxiety are negative thinking habits,” she explains.

The combination of chronic pain and being consistently in a negative mental state can have social and economic repercussions – difficult relationships, job loss, deteriorating social interactions – that can lead to further depression, stress or anxiety.

“A lot of the times, unfortunately, by the time I end up seeing people, they’ve already been struggling with it for a long time,” Overholt notes. “(A social worker) is not a first line of defence. The patient usually goes to their (health-care) provider… they’ll get prescribed some medications to help with the pain, but we know it’s a lot more comprehensive than that.”

Patient education also plays a role in the pain management paradigm. Understanding what goes on in their body, why they may be feeling such pain, how the body works and how the brain responds are all important information that needs to be communicated with the patient.

Explaining to the patients that even if sometimes, their physiological structure that’s causing the pain cannot be fully reversed – as in osteoarthritis cases – they can still return to normal activities of daily living with proper management and self-care exercises and protocols, Tupak says.

Patients at the Windsor-Essex PCLBP pilot site are encouraged to get involved in physical activity programs organized by the clinic, such as a walking group that meets once a week at the clinic.

“The increased physical activity is good for their back, plus the increased socialization,” Overholt says. The clinic also runs a six-week education program on coping with chronic pain, which covers physical activity, nutrition, relaxation strategies, visualization, deep breathing, and dealing with negative thoughts.

Pain and the opioid crisis

Opioid prescribing in Canada and the U.S. are among the highest in the world. In fact, it’s two to three times higher than in most European nations, according to a 2015 British Medical Journal clinical review, “Opioids for low back pain.” More than half of opioid users report having back pain.

There is now increasing consensus in the medical and the larger health-care community that opioids have been overprescribed in the past, while there is little evidence of its efficacy in resolving acute and chronic back pain. The long-term effects and safety of opioids is also still largely unknown. As a result, over the last several years there has been a concerted effort to reduce opioid prescriptions for non-cancer-related chronic pain patients.

Pain patient advocates, however, see this as an extreme measure that led to many pain patients, who have been dependent on opioid medication for function, suddenly being cut off.

“Lots of people have legitimate dependencies on opioid medication to function and there’s massive stigma around that,” explains Jennifer Hanson, director of education and engagement at Pain BC, a not-for-profit advocacy group in Vancouver helping people living with pain. “It’s important to acknowledge that not everybody who’s on opioid is an addict. They may be dependent (on opioid) but it is because they live a much better and more functional life.”

Some of those people, who have been dependent on opioid and suddenly been cut off from their prescription, have been forced to find the narcotics elsewhere – off the streets, for instance – and this is contributing to the rise in opioid-related deaths and overdoses, with fentanyl-laced illicit drugs making the rounds in these circles.

“There is an argument to be made that extreme restrictions have led to a kind of turn to illicit drugs because of no other options,” Hanson notes.

It is not currently known how much of the opioid-related deaths and overdoses are linked to this group of population. In fact, tracking the extent of opioid use and abuse in Canada currently consists of a medley of unstandardized provincial reporting, making it difficult to see a clear national picture.

One thing is certain, however, this growing public health crisis has the federal and provincial governments scrambling to catch up with strategies to address the issue.

Last November, the Government of Canada issued a Joint Statement of Action to Address the Opioid Crisis, in which a number of government agencies, professional associations, including the Canadian Chiropractic Association (CCA), and other stakeholder organizations expressed commitments “to act on this crisis,” working in their own areas of responsibility to “improve prevention, treatment and harm reduction associated with opioid use.”

Under the joint statement, the CCA commits to “developing evidence-based professional practice recommendations and guidelines to facilitate the appropriate triage and referral of Canadians suffering from chronic and acute musculoskeletal conditions and reduce reliance on opioid” by June 2017.

The CCA has declined this writer’s request for comment. No reason was provided.

In the provincial level, the B.C. Chiropractic Association (BCCA) is working with Pain BC to develop a workshop for chiropractors on the assessment and treatment of chronic pain.

Dr. Jay Robinson, president of the BCCA, says it’s important that chiropractors are on the same page, or at least “speaking the language appropriately” with other health-care professions to enable a more integrated approach to care.

“We reached out to Pain BC to create a training program so we are all on the same page when it comes to (chronic pain) patients. Being able to connect with other health-care providers and being able to speak the same language is crucial,” Robinson says.

Robinson notes providing additional training for chiropractors on chronic pain management is beneficial, given the fact that chiropractors typically see these types of patients in their clinics on a daily basis.

He also emphasizes the importance of starting with the least invasive treatment first when dealing with chronic pain patients, echoing the recent ACP clinical guideline on nonpharmacologic treatment of low-back pain.

“In the past, chiropractors would usually see a patient after they’re already an opioid patient. By that point, there’s often a great deal of comorbidity factors that make the case quite complicated,” Robinson explains.

Knowledge is power

Dr. Chris Carter, the chiropractor from Kelowna, B.C. recommends taking additional pain management courses to better equip chiropractors with tools and knowledge to effectively assess and manage chronic pain. Currently, there are two courses in Canada that offer this: a graduate certificate course at the University of Alberta and a similar one at McGill University, he says.

Short of taking additional courses on pain management, chiropractors and other health-care providers should, at a minimum, keep up-to-date with the latest research and clinical evidence pertaining to chronic pain, he says.

Having worked in Australia for a decade, Carter acknowledges chiropractic training at CMCC is among the best in the world.

“We’ve got great education,” Carter says. “In addition to our wonderful skills, we need to be reminded of the importance of assessing and managing patients through a biopsychosocial model.”

Case for expansion

It’s already established that integrating chiropractors into primary health care settings result in better outcome for the patients. This is especially true for back pain patients. The availability of chiropractors in a funded health care model provides medical doctors another treatment option for their patients, and helps “reduce the pressure on physicians to prescribe,” says Dr. Peter Emary, a chiropractor from Cambridge, Ont.

Over the last three years, Emary and several chiropractors in Cambridge have been running a part-time chiropractic clinic funded by and located at the Langs Community Health Centre in Cambridge, Ont. The health centre typically sees a demographic of patients with diverse chronic issues, and many of them are on opioids and other narcotics medication.

Emary and his colleagues have been collecting data and researching patient outcomes from the clinic. “One of the most interesting findings is that a large majority of our patients that follow up reported that they were able to reduce their pain medication.”

The Cambrdige chiropractor reported these outcomes in a poster presentation at the World Federation of Chiropractic Congress in Washington, D.C., last March.

“Integrating chiropractors into primary care settings, like community health centres, would be an excellent way that we could contribute as a profession to the opioid crisis,” Emary explains.

Health care integration is just one solution. Another potential remedy is scope expansion for chiropractors to allow them prescription rights, limited to conditions that chiropractors typically treat, such as back pain, neck pain and other musculoskeletal conditions.

Some in the profession are making a case for granting chiropractors limited prescription rights in the wake of a growing opioid crisis. They cite the Swiss model, where chiropractors in that part of the world have enjoyed an expanded scope of practice, including limited prescription rights for musculoskeletal conditions.

With limited prescription capabilities, Emary argues, chiropractors would then be viewed as primary spine care providers, and would be the first contact of patients for back pain.

“We would then be in a position to discourage patients from taking prescription-strength meds, like opioids, for back pain and inflammation. Instead, recommending our typical treatments like chiropractic manipulation, exercise, rehab and education,” Emary says. He adds, however, that any potential move to allowing limited prescription rights would require a change in the curriculum for chiropractic education.

The topic of limited prescription rights remains highly controversial in the chiropractic community, but one that needs to be debated, Emary says.

In the context of acute or chronic pain, there are instances when patients present at the doctor’s office or a chiropractic clinic in excruciating pain, a limited dose of pain medication may be appropriate for immediate relief or to help the patient cope and return to function.

“The reality is one of the strongest reasons patients transition from acute pain to chronic pain is because of uncontrolled acute pain,” Carter says. “That has been distinctly shown in research because of the development of central sensitization.”

When necessary, pain medications can lower the intensity of pain transmission to the spinal cord, therefore lowering the chances of developing central sensitization, Carter explains.

Prescription rights or not, a May 2016 study published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics may provide some perspective on the role chiropractors can play in addressing the opioid crisis.

The study, “A cross-sectional analysis of per capita supply of doctors of chiropractic and opioid use in younger Medicare beneficiaries,” found that the higher the number of chiropractors in a region, the lower the number of opioid prescriptions being filled.

(This article originally appeared in Canadian Chiropractor magazine.)

Print this page