Health News

Essentials of Assessment: Summer 2003

As I mentioned in my last article, we often ignore joints and their intrinsic structures as well as joint mobilization techniques that would be of benefit. The assessment of facet joint dysfunction, in cases of low-back pain, is a specific area that we often leave to other health care professionals.

September 17, 2009 By David A. Zulak MA RMT

As I mentioned in my last article, we often ignore joints and their intrinsic structures as well as joint mobilization techniques that would be of benefit. The assessment of facet joint dysfunction, in cases of low-back pain, is a specific area that we often leave to other health care professionals. The lack of knowledge about these joints and their dysfunctions in turn limits us in the use of techniques we have been taught or have at our disposal. We are often unsure of how to apply them safely and effectively because the nature of the impairment is not clear enough for us.

I mentioned in a previous article that when health care professionals attempt to locate the source(s) of low back pain, the statistical average is very poor: at best the causes will be found only 20 per cent of the time. Note that I use the plural: causes, sources.

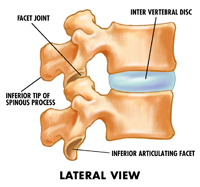

The lumbar spine structures, like those of the whole spine, are tightly inter-related. Almost any motion in this area of the spine is controlled by the interplay of the shape of the osseous structures, the tissue structure and physiology of the discs, ligaments, muscle and fascia.

These somatic structures (versus radicular or neural structures) are rarely dysfunctional without some of the other tissues being injured and having musculature neuroreflexively stimulated to splint the area.

If the elements of the lumbar spine (the “motion segment” – two vertebrae and the joints and structures between them) are held misaligned for some time, this results in tissue deformity (some shortened, some lengthened) that can make the proverbial “chronic low back pain” so difficult to sort out.

We are often left without a clear idea about what to do or treat first: lengthen this, strengthen that, mobilize hypomobile joints and allow hypermobile joints supportive tissue to shorten … ?

For massage therapists, the missing element in our assessment of the low-back is often the motion assessment of the facet joints (correct term: zygapophysial joints).

Without these tools our chances of even being in that 20 per cent range is wishful thinking on our part.

Most North American osteopaths refer to two basic categories of dysfunction of the facet joints in the

lumbar joints: “neutral dysfunctions” and “non-neutral dysfunctions.”

To simplify, we can look at neutral dysfunctions being so named, as they are present or observable in the neutral position of the lumbar spine.

- They usually remain visible in either flexion or extension as well.

- They are considered a “group dysfunction” as several vertebrae are involved.

- There is usually an imbalance or dysfunction below (and possibly above) the group neutral dysfunction that is the precipitating cause.

For example, an unlevelled sacroiliac base (i.e. from a leg length discrepancy, or a unilaterally rotated pelvis) may set up or precipitate a group dysfunction in the lumbar spine – much like a functional scoliotic curve. This could also arise from unilateral spasming muscles such as the quadratus lumborum or deep intrinsic muscles of the back (rotatories etc.) that rotate and side-bend the vertebrae into the rotoscoliotic curve.

|

|

|

|

However, unlike a functional scoliosis, the group dysfunction does not disappear when the client changes position. It has progressed to being a dysfunction that is now self-sustaining, it does not necessarily disappear after precipitating causes are removed; it remains observable through flexion and extension, and is itself responsible for measurable losses of range of motion in the lumbar spine. It could now be a precipitating cause for some further changes in function of the low-back, thoracic spine, or pelvis.

These neutral dysfunctions often have precipitating causes that need to be corrected first (i.e. correction of a unilateral pelvic tilt) and then the ‘neutral dysfunction’ can be addressed (by lengthening a QL and appropriate rotatories, etc.) This order of approach will subsequently sustain its correction.

The testing for this neutral dysfunction (sometimes called Type I dysfunctions among Osteopaths) is a mixture of observation and palpation.

With the client standing (or seated on a hard stool) observe and palpate the lumbar spine area. We are

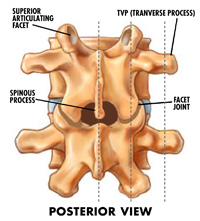

looking for the telltale signs of scoliosis: a ‘fullness’ on one side of the spine traveling parallel off to one side (over where the TVPs (transverse processes would be.) The spinous processes of the affected lumbar spine will show the telltale curve.

This fullness present comes from the rule that; side bending and rotation of the lumbar vertebrae are coupled. In the neutral position they are coupled into moving in opposite directions: they side-bend to one side and the (anterior surface of the) vertebral body moves the opposite way. For example: if the vertebrae are side-bending towards the right, then the vertebral body turns to the left. This results in the left TVPs of the affected vertebrae being moved posteriorly and the muscle and tissue behind them gets pushed back and creates the fullness that can be seen and felt on the one side (on the convex side of the curve).

As we’ve mentioned, the neutral dysfunction of facets is seen and felt during the client in the neutral position. It remains so whether the client now bends forward or hyper-extends the back. The therapist can view the neutral position with the client standing, sitting up straight on a hard stool, or lying prone on the massage table. Flexion is best done on a stool; as hip flexion is mostly used to flex the hip 90 degrees for sitting, and in most people they will quickly use up the rest of their hip flexion in bending forward and then the rest of the motion in forward bending that is left comes from the back.

Further, we can have the client hyper-extend while prone on the table in what is called the ‘sphinx position’ and again see if the fullness is present.

The second type of facet dysfunction that osteopaths speak of is “non-neutral dysfunctions” (Type Two). This usually refers to a single joint dysfunction, where a facet joint of the spine does not open as it should, or will not close, as it should.

The suspicion is that these dysfunctions occur when the spine is not in neutral position, but rather occur when the spine is already flexed or extended and then has rotation or side-bending movements added.

|

|

|

|

The spine in a non-neutral position, (meaning it is already flexed or extended prior to the addition of other movements), does not have neutral mechanics – the motions of rotation and side-bending of vertebral bodies are not coupled in opposite directions as has been described for the spine in neutral position.

Rather, if the spine is first flexed and then side bending is added, with the coupled rotation now to the same side, then the facet joints through which this is happening are taken into the extremes of an opened position (i.e., flexed ‘open’ and then has rotation with side-bending added).

Taken to the end of their range and slightly beyond what is good for them, the joint capsules and supportive ligaments along with the deep layer of intrinsic muscles become stretched and strained. This is a Flexed-Rotated-Side-bent (FRS) dysfunction.

The other possibility for a type II dysfunction is when the spine is in extension and the addition of rotation and side-bending are added, and too great a force closes the joint, ‘jamming’ it, causing an inability to open. This is an Extension-Rotation-Side-bending (ERS) dysfunction.

In either situation, the intrinsic structures of the joints (fat pads, joint folds, meniscoid pads …) could get jammed between the surfaces, or get dragged out of place with excessive flexion causing pain, and spasm (a neuroreflexive reaction in spinal muscles) in a manner that does not allow the joint to move away from this position1. The client may feel pain (a pinch) that may stay or fade.

This ‘stuck joint’ then has multiple consequences for the motion segment of the spine of which it is a part, and with a high possibly for others above and below2. This, of course, includes setting up a neutral dysfunction above the non-neutral dysfunction. I.e., L4-L5 type II, as well as a group dysfunction, type I, in L1-L4.

TESTING: To test for “type II – non-neutral dysfunctions” palpate gently over the articular pillars of

the lumbar spine (which are about a finger width to either side of the spinous processes).

Ask about tenderness and note any asymmetries: for example, a swollen apophysial or facet joint capsule. These feel like a large pea and have been described as “bony knots”3 (when the capsule is fibrosed).

To test the lumbar facets for “non-neutral dysfunctions” have the client seated on a hard stool in front of you. Landmark the ‘disc space’ between L4 and L5 (i.e., where a line from the top of the iliac crests crosses the spine). From here we can count up or down to locate the appropriate vertebrae’s spinous process. Note that the transverse processes (TVPs) are approximately on the same level as the discs. The TVPs are palpable an inch or more laterally out from a vertical line made by the spinous processes.

In general, the lumbar TVPs can be landmarked by first finding the space between the spinous process of the lumbar spine and moving about an inch laterally from the inferior portion/tip of the spinous process (of say L1) which will give you first (at a finger width from the SP) the facet between the two vertebrae (in this example L1-L2), and another finger width or so is the TVP of the next lower vertebrae (L2).

If you palpate the lowest portion of the SP of L1 and slide out a half inch or so on either side, you will be over the facet joints for L1-L2. If you go a bit further (usually on the outer edge of the bulk of the paraspinal erectors) and sink in, you will be over the ends of the TVPs of L2. You should be looking for asymmetries when palpating in neutral, full flexion and hyperextension.

Assuming for the sake of argument that all is basically symmetrical with the client sitting with the spine in neutral, have the seated client flex forward as far as possible for them, and then palpate the TVPs4. (Land-marking and counting as above.)

If on palpation the left TVP of L2 is more posterior and slightly inferior then on the right it may well be that the left facet of L2-L3 is failing to open5. Note: the TVP that does not ride up as high as its partner, points to the dysfunction of the facet joint below that TVP. This means that the facet joint at L2-3 on the left remains closed, (‘extended’) while the rest of the spinal segments and joints are flexing. Further, this fixed-closure is causing that vertebrae (L2) to rotate and side-bending to the left. (An ERS – L at L2-3)

So, with flexion we are looking for problems with facets remaining closed or ‘extended.’ The posterior TVP is found on the same side as the dysfunction. (Note: the asymmetry disappears on extension, as all facets are closed or extended.)

Now, let’s assume that no asymmetry was found in flexion (there was no ERS-dysfunction). With the client now lying in prone position, have them raise their shoulders, chest and head up off the table (while the abdomen remains on the table) and rest on their elbows, with their chin in the palms of their hands (the sphinx position). Remind the client to relax the abdomen and low back.

As we landmark and palpate the TVPs we note that with one pair of TVPs, those belonging to L2, the left side appears to be more posterior and slightly inferior when compared to its partner. This implies that the facet on the opposite side, the right facet joint of L2-L3 will not close.

It is being held opened while the rest of the joints close. This facet joint of L2-3 on the right being fixed opened (flexed) while all other facets are closing during extension results in the vertebrae above (namely, L2) to rotate and side bend to the to the left. (The segment is FRS-L at L2-3)

Thus with hyperextension we are looking for problems with facets remaining open or flexed. The posterior TVP is found on the side opposite to the dysfunctioning facet. (Note: the asymmetry disappears on flexion, as all facets are opened or flexed).

The palpation of the TVPs takes a little practice, but comes quickly to MTs as palpation is what we do all the time! None the less, the TVP of L5 can be elusive buried deep in muscle and connective tissue structures.

Philip Greenman D.O. suggests at best the L5-S1 facet itself is more easily palpated for motion alone.

What to do with what you find?

- Type I, neutral dysfunctions, usually require treatment of elements or tissues that are the predisposing cause of the group dysfunction. Then the sustaining intrinsic structures and tissues are addressed.

- Type II, non-neutral, usually respond to direct treatment on the joint or intimate structures that regulate that individual joint’s motions.

Joint play, stretching, positional release, myofascial all have their place. And, I described in my last article an application of joint mobilization for opening and closing facet joints in the lumbar spine.

However, the premier method of dealing with these types of dysfunctions is Muscle Energy: It positions the client’s joints so that the intrinsic ligaments and joint structures are ‘pressuring’ the joint to move in the manner you would wish and then with the addition of the contract-relax technique the offending splinting muscles are relaxed and the joint moves into its correction.

Osteopaths prefer to use muscle energy techniques to mobilize or free facet joints, and only if this method fails do they resort to high velocity low amplitude thrust techniques (much as a Chiropractor might use.)

Remember, we may not have necessarily found the cause of all our client’s low-back pain, but we may have addressed an important piece of the puzzle. Happy hunting!

References

- Or, a joint structure may get overstretched and injured, the capsule, a ligament, or a component muscle my be strained and then spasm … A similar series of events can occur in extension, where a facet joint becomes ‘jammed’ into a closed position – due to compression of intrinsic joint materials, and the over shortening of muscles going into spasm and ‘locking’ the joint closed.

- Any dysfunction of a zygapophysial joint leads to consequences with surround zygapophysial joints and to the appropriate discs. And visa versa.

- A descriptive term favoured by Erik Dalton.These ‘bony knots’ can be swollen or fibrosed facet joint capsules, that may need to be frictioned in order for the tissue to be able to allow the movement required to regain full ROM.

- In reality the client would often side-bend and rotate away form a tender/painful facet ‘locked closed’. Hence this positioning should be noted when seen. Further, if the dysfunctions we are about to investigate are minor, they do not appear in the neutral position, but only as described below. However, if the dysfunction is major, then some asymmetry will be apparent in neutral.

- No, this is not fuzzy math!

Print this page