Features

Continuing Education

Education

Fascial Treatment

There are many things to study when learning the art of fascial treatment – and the most important is “anatomy.” If you do not know where to place your hands, no technique in the world will work consistently for you.

September 16, 2009 By Brad McCutcheon

There are many things to study when learning the art of fascial treatment – and the most important is “anatomy.”

If you do not know where to place your hands, no technique in the world will work consistently for you.

Each of our patients has certain anatomical differences that we have to appreciate in order to customize each treatment to their bodies.

|

|

|

|

When teaching a cadaver lab two years ago, we had four different bodies to work on. Of these four bodies, only two of them had pectoralis minor insertions on ribs 2 to 4 while the other two had insertions as low as rib 5 and one had no insertions at all until ribs 4 and 5.

This slight difference can create changes in the effect your techniques will have when treating fascially. It may also explain why anatomy texts differ about origins and insertions.

Instead of describing certain techniques in this article, I have decided to give some general anatomical guidelines for treating fascia in the cervical spine. I cannot guarantee that anyone will be able to reproduce a technique by simply reading it.

Those of you with educated hands will be able to use these rules to help your practice. Those of you who are educating your hands will be able to have some anatomical guidelines to practice with.

There are many authors of fascial anatomy. Tom Myers, a rolfer from New England, has a manual for MTs called Body cubed. The Endless Web was written by Feitis and Schultz and is an excellent reference for body

patterns. If you read French, Paoletti wrote an excellent manual called Le Fascias in which fascial chains and embryology are explained. The list goes on. I encourage you to find a variety of anatomy text sources.

Anatomy, like any other topic, is subject to bias. If all your sources for anatomy are medical, you will get the medical bias of information. Fascia is seldom mentioned and easily overlooked.

If you find sources from rolfing, osteopathy and physical medicine for your anatomy, you will be enlightened by another viewpoint closer to what you are finding in your patients.

Pain and anatomy: Sites of pain are not always areas of restriction. Pain, as we understand it, comes from chemical mediators that irritate nerve endings or compress their capsules causing them to fire and send signals to the brain.

Chemical mediators are caused by inflammation. Inflammation is caused by torn or stretched tissue and is therefore usually located at the hypermobile or adapting structures. If an area in the body is blocked, another area will have to move more than normal to allow for mechanical motion. This second area will inflame and tell the patient about the pain.

The only exception to this is compression pain (dull achy pressure type pain) that comes from scarred tissue at the restricted site. The point is … don’t jump to conclusions regarding the origin of pain.

Fascial chains: There exist chains of tissue closely linked by their embryology, energy flow and anatomical connections that will create lines of tension and complicate an existing condition. In order for an area to stay mobile the entire chain will have to be addressed and treated.

Tom Myers calls these chains anatomy trains, Struff Denyss calls these chains fascial chains, Mitsuki Kikkawa, the originator of Suikodo,calls these chains muscle chains and relates them to meridian dysfunction.

If you notice a recurrent pattern in a patient’s condition, it may be a fascial chain that is responsible. Keep in mind the existence of these fascial chains.

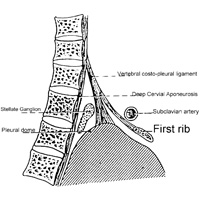

In the C-Spine remember that the majority of the fascia that causes trouble is on the anterior surface. There are 3 layers of fascia – the superficial, middle and deep cervical aponeurosis. (Plate 30 of Netters Atlas of Human Anatomy gives good visuals). Netters calls these the superficial investing fascia, the Buccopharyngeal fascia and the Alar fascia respectively.

You will find them invested in the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments. Unlike the deep longus colli stripping that is painful, all of this fascia is reachable and treatable without pain.

Three questions to ask yourself:

1) How do you contact a structure on the anterior part of the vertebrae without placing your fingers on the tissue?

2) Where on this long structure do you place your hands?

3) How long do you hold for? The deepest aponeurosis (DCA) runs from the inferior surface of the sphenoid bone behind the nasal region and travels inferiorly and posterior to the trachea. Place your hands on the occiput by cradling the back of the head. Remember to keep the head neutral, no flexion or extension. Place the other hand on the sternum above the sternal manubrial notch and lean back with your body bringing the occiput with you gently. Feel for tension between your hands and ask the patient where they feel it.

The process will take about 2-3 minutes to release depending on the patient’s tissue, but the feeling in your hands will be lengthening without physical movement.

The first release is the warming of ground substance and not the lengthening release you desire to create permanent change. Wait for a second and sometimes third release to create permanent change.

General guidelines for cervical spine fascial treatment are:

1. Anchor the tissue between your hands before you add tension;

2. Use your body to create the tension so that your hands can relax;

3. Wait for the ground substance to release and wait again for the tissue to change in length.

All whiplash type injuries require deep anterior work. The thyroid gland is embedded in this anterior pre-tracheal fascia and its blood supply can be cut off by tension here.

Don’t forget that many of the fascial structures run through the cervico-thoracic junction and continue into the mechanics of the thoracic region and lungs. The scalenes’ fascia articulates with the pleural domes of the lung. Lesions of the first three ribs can directly affect the lateral flexion of the cervical vertebrae. The deep cervical aponeurosis can be tightened by a coughing spell.

After a cold, patients may complain of a tight, stiff neck and headaches. Freedom of this structure will allow them to avoid muscular contraction causing trigger points and tension headaches. You do not have to free up all this tissue but tightness in one structure can bring back tension in another. So, re-assess following each treatment to determine your effect.

This procedure is simple and it will help to unlock the cervical spine, saving you treatment time. Think like a therapist when reviewing anatomy. Discover how to reach a structure that you cannot place your hands on. Increase your knowledge by taking a fascia-based anatomy course.

I wish you all great success in your practises and ask that you “Don’t forget the FASCIA.”

References (in order)

1. Myers, Tom. “Body 3 A Therapists Anatomy Reader” Reprints from Massage Magazine 1997-2000.

2. Feitis and Shultz. “The Endless Web” North Atlantic Books, 1996 Berkeley California

3. Paoletti, Serge. “Les Fascias” Sully Editions, Vance Cedex, France 1994

4. Netters, Frank. “Atlas of Human Anatomy” Ciba-Geigy Corp, 1989 Summit New Jersey

5. Kikkawa, Mitsuki. “Suikodo Part 1” 2002 ICTTM Schools Course Manual

6. McCutcheon, Brad. “Fascial Integration

a Fascial Assessment and Treatment Manual for Massage Therapists” 1995 Brace Education Seminars

Print this page