Health News

Clinical Somatic Education, Part 1

Clinical Somatic Education: A New Discipline in the Field of Health Care, written by Thomas Hanna in 1990 to elaborate on the work he created and practiced, still has great significance today for practitioners.

January 4, 2012 By Andrew Teufel RMT

Clinical Somatic Education: A New Discipline in the Field of Health Care, written by Thomas Hanna in 1990 to elaborate on the work he created and practiced, still has great significance today for practitioners. He titled it A New Discipline in the Field of Health Care because it was written during the inaugural summer of his first training program. The article was published in the 1990 fall/winter issue of Somatics Magazine of Mind/Body Arts and Sciences. In 1990 he also published his book Somatics and, tragically, died in a motor vehicle accident that summer before he was able to deliver the complete three-semester somatic training program. Now, more than 20 years later, in this two-part article we will explore the system he created and some developments and divergences that occured along the way.

|

|

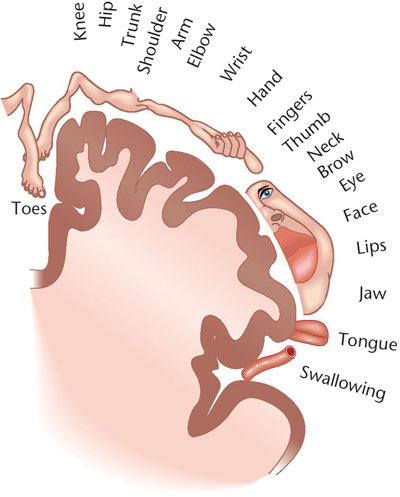

| Image 1: An illustration of the distribution of motor information in the central area of the brain.

|

BUT FIRST, SOME HISTORY

Thomas Hanna, PhD, was a pioneer and legend even as he lived. A philosopher and educator, he taught ethics to medical students at the University of Florida in the late 1960s and early 1970s. While teaching at the University of Florida he also studied neurophysiology. Hanna married Eleanor Criswell, PhD, who was a professor of yoga psychology at Sonoma State University. Hanna holds the record for teaching of one of “the largest Yoga classes ever given.” This class was held at the University of Florida, Gainesville campus, with seven hundred students in attendance, in 1972. In 1975, Hanna hosted the first North American Feldenkrais training course as the director of the Humanistic Psychology Institute in San Francisco. In 1978, he hosted the Explorers of Human Kind Conference in Los Angeles, California, which featured lectures by Moshe Feldenkrais, Hans Selye, Ida Rolf, Alexander Lowen and others.

Just as his life was amazing, so is the work dealing with clinical somatic education that he left behind. In his 1990 book Somatics, Hanna offers five case studies that examine some of the wonderful changes people have experienced from clinical somatic education. Let’s now move on to examine his concepts and methods.

SOMA

Hanna redefined the mind/body dichotomy by defining the soma (a body) as “the body sensed from within.” When we look at others, we see a body. When we pay attention to ourselves we have a soma or somatic awareness. Soma, under normal biological consideration, is a body, however, a human soma can have consciousness. Preferring to see people/somas/bodies as capable conscious beings is what allowed Hanna to teach his clients about the two nervous systems that operate the muscular system: the autonomic nervous (ANS) and the somatic nervous systems (SNS).

The ANS governs our sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Gastrointestinal, cardio-respiratory and other glandular processes are the more commonly recognized functions of the ANS. More uncommonly considered functions of the ANS are: unconscious neuromuscular contractions to stimuli (reflexes– startle, Landau and trauma); our habits of sitting and standing; and the use of the dominant hand, leg, eye, ear, etc.

SNS SOMATIC CORTEX OR SENSORY-MOTOR CORTEX

The somatic nervous system (SNS) gives us conscious control of our neuromuscular and myofascial systems. The SNS is a sensory-motor system. Another way to say this is that the brain senses movement and we, then, become more conscious of our bodies. At the centre of the human brain are tracts known as the somatic cortex or sensory-motor cortex.

UNCONSCIOUS TENSION/SENSORY-MOTOR AMNESIA

The impulse for unconscious neuromuscular contraction to stimuli (reflexes) occurs below our conscious awareness by the regions of the hindbrain. Examples of this type of unconscious tension would be the startle, Landau and trauma reflexes (i.e., the pain-tension cycle). The residual tension, or involuntary contraction, held in the neuromuscular system was dubbed sensory-motor amnesia (SMA) by Hanna. SMA is a state of forgetting how to sense and control certain muscle groups or neuromuscular patterns.

Hanna helped to a clarify that the somatic/conscious control can help turn off the involuntary/ANS muscular spasm and tension through movement and education. If an individual can sense the muscle that is contracted 40 per cent, then by contracting it to 40 per cent a person can lower the muscle tension from 40 per cent to 30 . . 20 . . . 10 per cent and eventually to a state of complete relaxation. Clinical somatic education teaches voluntary control to bring about the release of the neuromuscular system and myofascial systems.

OUR PRIMARY MUSCULAR REACTIONS TO STRESS

Normally, when we think of the effects of stress, we think of the results on our heart, organs, mind, emotion, the chemistry of adrenalin and other hormones. Seldom do we consider the effects on the muscles, joints, posture and how this may influence fatigue and pain. As practitioners who focus largely on muscle and joints, RMTs should know the stimuli of the primary reflexes and their muscular and biomechanical effects that contribute to pain and stress.

STARTLE REFLEX – THE STOOPING BODY

Known as the Red Light reflex to somatic educators – because of its power to stop an individual – this reflex can keep a person frozen in muscular tension, heart rate and respiration so powerfully that it is difficult for the individual to be aware of any other sensory information. It is the “freeze” in fight/flight/or freeze that occurs in our bodies in the event of stress. This reflex is a protective response to negative events ranging from overt danger to vague apprehensions.

This lifelong primitive reflex closes muscles over the abdomen and hunches shoulders via an over-activated trapezius, creating a stooped posture. This involuntary reaction to loud noises, anger, depression, apprehension or fear begins with a cascade of impulses originating in the primitive hindbrain. The stooped posture typifies the “Myth of Aging,” or what society considers typical for seniors. In the stooped posture, we see kyphosis of the spine, forward head posture, reversed breathing from the chest instead of the belly, and tightening of the jaw, hands, adductors, hamstrings and feet.

LANDAU REFLEX – THE ARCHING BODY

People are always surprised to learn that they are doing something they weren’t aware they were doing. Similar to the startle reflex – which results in cringing of our muscles at our neck, shoulders and abdomen in response to apprehension – there is another full-body reflex, but this one is stimulated by the command to action and affects the muscles on the posterior side of the body. It is called the Landau reflex.

The Landau reflex is known as the Green Light reflex by somatic educators because this reflex is stimulated when we go, push forward and accomplish. This involuntary reflex is overstimulated today with the fast and always-moving-forward pace society keeps. This reflex tightens the paraspinal muscles and hip extensors. The contraction of these muscles are coupled with synergistic contraction in the neck and shoulders, and the hips and legs. From the lateral view, it presents as an overarched back and shoulders extending past the hips, as if the individual is ready to push forward or is just tense in the back.

When you look at military personnel or athletes, you see the Landau reflex. I have met tall men with their shoulders past their hips seven to eight inches and they are always amazed to discover this.

An infant is born helpless, using its frontal flexion muscles to cling to its mother. Later, at about two or three months, the baby discovers it can lift its head while lying prone. This new adventure of lifting the head allows the infant to see farther and this whets the appetite for more. This lifting of the head then becomes arching the back and eventually thrusting itself forward along the floor, the Landau reflex. The contraction of the extensor muscles of the lumbar spine and hip muscles have two main effects: it teaches the baby to go forward and it teaches the baby to go up. Over the next eight to 12 months, the infant uses these same muscles to sit, then stand and eventually walk.

TRAUMA REFLEX – THE TILTING BODY

This reflex is also known as the pain-tension cycle. Whenever there is pain or injury, there is the involuntary bracing and holding of the injured area. This type of holding is reflected when observing the body from the anterior and posterior views, presenting as a tilt. If a person has an injured foot, knee, hip, shoulder, arm, etc., it is reflected in bracing, tilting and using the other limb more. This tilt is a functional scoliosis and, if held long term, creates a list of other symptoms and maladies.

For somatic educators, this lateral shift of muscular tension of the largest muscles can be a contributing factor to frozen shoulder, chronic unilateral pain, headaches, temporomandibular joint disorder, leg length discrepancies and low back/pelvic/sacroiliac joint pain.

SOMATIC CENTRE AND SOMATIC EDUCATION

The motor Homunculus (Latin for “little human”) in image 1 is a graphic illustration of how much more we are aware of our hands than our trunk. About 30 per cent of our somatic awareness is at our hands and less than 10 per cent is at our trunk.

The clinical somatic education system begins with this important concept of how little we sense, and can or cannot control, the trunk. Clinically, the trunk is likely our primary focus – it is the location where the greatest amount of pain and discomfort are experienced in our clients. The three reflexes we have examined in this article affect the centre enough to distort body alignment and change the ability for an individual to control the trunk.

Biomechanically and energetically, the trunk needs great consideration: it houses our organs; it houses the central nervous system; it has the least awareness of any other body part (as illustrated); it has the largest and most powerful muscle groups; it is the nexus of upper- and lower-extremity movement; and it is the location of the centre of gravity.

Many other modalities have terms for the trunk – somatic educators know it as the “somatic centre.” Other terms for it are “the core,” and, in oriental philosophies, “hara” and “sushumna.” It is the region where the flow of movement and energy begins for our life force.

In Part 2 of this article, I will discuss the components of clinical somatic education; present a brief case study; and explore the application of clinical somatic education in a busy RMT and yoga practice.

Sources used for this article

- Biofeedback Graphs, Bio Research Institute, Santa Rosa, California. 1997

- Hanna, Thomas. The Body of Life-Creating New Pathways for Sensory Awareness and Fluid Movement. Healing Arts Press, Rochester, Vermont 05767. ©1998, 3Rd Edition.

- Hanna, Thomas. Somatics-Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health. Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Ma 02142. ©1988.

- Knaster, Mirka. A Somatic Approach to Yoga, Yoga Journal. July/August 1992.

- Homunculus, Long, Ray MD FRCSC and Chris McIvor. The Key Poses of Hatha Yoga, Scientific Keys Volume II, Bandha Yoga, ©2008 Raymond A Long MD FRCSC

- Sensory Motor Homunculus Image, QuantumConditioning.ca

|

Andrew Teufel has been an RMT for 20 years. He is certified from the Novato Institute for Somatic Research and Training, a Yoga teacher and a former RN. He has been providing continuing education for RMTs in somatics since 1997 and is the creator of Applied Somatics and Applied Somatics Institute. Andrew is a presenter and consultant to private and public businesses and groups.

Print this page