Features

Collaboration

Practice

One Blinded Soldier

The development of massage therapy as an organized form of physical treatment reached its ‘golden era’ as a result of advancements in anatomy and physiology.

September 25, 2009 By Emily E.S. Cowall Farrell MT DHMSA

The development of massage therapy as an organized form of physical treatment reached its ‘golden era’ as a result of advancements in anatomy and physiology.

Men who belonged to the medical elite from antiquity to the 19th century predominantly authored literature about massage practice.

Although massage and physical forms of treatment have origins in ancient practices throughout the world, enlightenment Europe of the 17th century and the era of the ‘New Science’ would be the important turning point for massage as it is practiced today. From this point onward, massage practice in Europe embarked on a path toward sophisticated art and science.1

The study of the organization of therapeutic massage practices in 19th century Britain provides linkage between the frameworks of professional massage developed throughout Europe at the intersection where WWI would catapult this model of practice into the Dominion of Canada. One blinded soldier remains the outstanding inspiration for a post-war generation that followed.

The study of the organization of therapeutic massage practices in 19th century Britain provides linkage between the frameworks of professional massage developed throughout Europe at the intersection where WWI would catapult this model of practice into the Dominion of Canada. One blinded soldier remains the outstanding inspiration for a post-war generation that followed.

The New Science Of The Enlightenment

The introduction of the knowledge of the presence and mechanism of valves in the veins in the 17th century challenged the previous Greek medical understanding of circulatory anatomy and physiology.2

Galen of Pergamum (AD 129-216) advanced early Greek medical knowledge dating from the 5th century BC into anatomical and physiological frameworks during his career spanning AD 157 to his death in AD 216.

In every aspect, Galen (pictured at right) and his concepts dominated medical thinking for 1500 years. The age of enlightenment and the soon-to-follow new science would initiate challenge to Galenic authority.

In 1603, at the University at Padua, the Italian comparative anatomist Fabrizio (1533-1610) studied previous discoveries by anatomists with a focus on describing the action of anatomical parts.3

Fabrizio described venous valves in his most significant work, De Venarum Ostiolis [On the Valves of the Veins], theorizing their action in preventing the extremities from being flooded with blood and permitting the distribution of blood to the entire body.

His work would later provide a crucial foundation to William Harvey’s investigations which were published in 1628 under the title of Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus [An Anatomical Disquisition Concerning the Motion of the Heart and the Blood of Animals].

His work would later provide a crucial foundation to William Harvey’s investigations which were published in 1628 under the title of Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus [An Anatomical Disquisition Concerning the Motion of the Heart and the Blood of Animals].

Controversial and disputed, the introduction of a new physiology and the numerous discoveries rapidly emerging during the 17th century were viewed as an assault to medical and scientific convention. Nonetheless, ancient treatise eclipsed, and a movement toward modernity rushed in.

This turning point has significant relevance for the practice of massage in a therapeutic format. New concepts of physiology provided an important ‘backbone’ rationale toward a tangible ability to define the effects and use of manipulations based in physiological mechanisms, ultimately enabling science to define massage technique though evidence based reasoning.4

In his 1889 book titled Massotherapeutics or Massage as a Mode of Treatment, Dr. William Murrell, lecturer, physician and examiner in Scotland and England, defined massage as ‘the scientific mode of treating certain forms of disease by systematic manipulations,’ asserting an emerging philosophy that certain manipulations of the soft tissues of the body when applied systematically would produce desired responses and physiological outcomes.

This text is not in isolation; various European physicians, physiologists, surgeons and specialists in physical rehabilitation would author similar publications throughout the 19th century that would re-iterate, change and advance this philosophy. Scientific rationale for massage formed rapidly by the 1880s.

Effleurage, one of the most consistently defined manipulations described in all of the literature, is directed toward the heart, promoting venous return; a solid definition defended by the evidence of Harvey’s contribution to the expanding knowledge of the anatomical and physiological role of valves in veins.5

The Chartered Society: Professional Massage In Britain

In 1894, 12 British women founded the Chartered Society of Massage and Medical Gymnastics, emerging from their positions as nursing sisters and nurse masseuses in hospital rehabilitation departments, to create a professional organization and standardization of the training criteria for individuals who performed massage therapy treatment prescribed by physicians. This effort to organize was in response to a perceived social need to place remedial massage practice into a respectable professional status, separating it from masseuses providing massage that was considered to be of ‘of very doubtful character’ or associated with activities usually conducted at bawdy houses.

The massage scandal of the summer of 1894 exemplifies the intersection between massage as a therapeutic practice and massage as a component of the sex trade industry. Popular papers and the highly respected British Medical Journal unleashed articles on the reports of London massage parlours, ‘concerning massage houses or the pandemoniums of vice.’ Demands for compiling a register of certified masseuses and methods to distinguish prostitution from legitimate therapy abounded.

On the side of prostitution, underpaid masseuses were challenged in employment situations where expectations were to be ‘favourable’ to male clients. Britain’s controversy was not in isolation. Reports at that time can be found in the Americas, and in particular Chicago, that blatantly informed readers of the masseuse’s talents for hire. At this time, terms such as ‘Madame’ as the great overseer of the ‘Girls,’ and pet names such as ‘Nurse Dolly’ or ‘Nurse Kitty’ for women who would perform the desired favours links a strange interconnected view of therapeutic roles.

Women providing massage and nurses have been equal targets to the slanderous attitude of implied prostitution.6 Oddly, British humour, even to this day, portrays the nurse as a scantily clad, fishnet stocking, bosom-bearing ‘angel of mercy’ and the masseuse as either ready to please or as the enormously large bodied woman of ethnic origin, delivering a pummelling blow.

Regulating the professional practice of massage therapy in Britain became formalized through the implementation of approved training facilities; usually attached to hospitals with massage departments or orthopedic facilities, core curriculum, standards of practice and definitions of professionalism all emerged in the structure of the Chartered Society. Credentials of teachers and method of examination were held to a critical standard. The contribution of textbooks that supported this model provided a strong evidence base to practice. This marks a second significant shift in the development of massage therapy.

Female authors, women who were experts in the training and application of massage and remedial gymnastics, were now supplementing the otherwise male-dominated literature base.

The literature authored by the women in this field would conform to the goal of achieving standardization, and rules and regulations and at the same time, support the institutionalized role of the masseuse.

Two of the founding members of the Society, Margaret Palmer and Louisa Despard, would author and publish textbooks from 1901-1916 that were suitable for candidates in training who desired entrance to practice as members of the Incorporated Society of Trained Masseuses.

In 1910, Palmer’s, Lessons on Massage was translated into Braille.7 Many of the Chartered Societies’ founding members and instructors at the training institutions would author textbooks on massage, hydrotherapy and remedial gymnastics.

World War I

Dr. James Beaver Mennell became associated with the Society and

its members in 1907. Mennell was a physician, physicotherapist8 and lecturer at St. Thomas’ hospital in London who was experienced in both theory and practical application of massage. His textbooks would be among those that further supported the institutional popularity of remedial massage with a particular focus on orthopedic rehabilitation.

In the first decade of the 20th century, remedial massage in Britain was becoming a respected therapeutic treatment. Fully involved in the care of wounded soldiers from the beginning of the war, James Mennell focussed on supporting his military involvement and newly assigned duties as medical officer in charge of the massage department of the special surgical hospital at Shepard’s Bush by authoring a series of textbooks outlining treatment care programs and regimens suited to military rehabilitation centers. Sir Robert Jones, the Inspector of Special Military Surgery, introduced the first edition of James Mennell’s 1917 text, Massage: Its Principles and Practice, with a declaration recognizing massage as an undisputed component of orthopedic care to the wounded.

“The value of massage as an aid to the orthopedic treatment of our wounded is now too well-established to require defense.” This endorsement by the military would take the remedial massage profession on twodistinct and vital paths.9

In the first instance, at the onset of WWI in 1914, remedial massage would be employed in the direct care of soldiers, both in hospitals servicing the wounded throughout the United Kingdom and at the outpost orthopedic centres which were an extension of makeshift field hospitals in the battle zones.

In a 1918 report from the Canadian Medical Services Commission, 33,795 Canadians were in hospitals in the United Kingdom. Breaking down the total number: 18,367 were in Canadian hospitals and 15,428 remained in British hospitals until their transfer home in March of 1919 reduced the numbers to 1465.

It is estimated that nearly 2000 soldiers were treated daily with massage, 200 by hydrotherapy and 2940 by remedial training at this time during the height of the conflict.10

The demand for nurse masseuses and nursing sisters overwhelmed and depleted the resources of the British trained society. The Canadian Medical Service would respond by establishing a training centre based in Toronto and Bexhill, England, where women and men were trained in massage therapy. This massage school was

a division of the Military Hospital Commission Command. The Toronto class of 1917-1918 graduated 70 women and six men.11 Trained in the same model and standards as their contemporaries in Britain, continuity was entering into care, driven by the demand for trained personnel to join in the war effort.

The Canadian-trained masseuses and masseurs were sent overseas to fulfill the demand for trained servicewomen and men; at the time of Armistice there were 1,901 nursing sisters and 1528 officers overseas. Canada established its own base of military hospitals that would receive veterans who had been stabilized overseas and then shipped back home for continued care.12 Centres, such as the Dominion Orthopedic Hospital on Christie Street in Toronto employed 74 masseuses on staff in the massage department providing care to homecoming soldiers.13

Massage therapy would become a form of treatment used extensively in orthopedic rehabilitation during the war and afterward provided opportunity for a meaningful return to civilian life; training in massage therapy was offered as a suitable career choice for blinded soldiers.

Occupational Massage Training Program: St. Dunstan’s Hostel

In London, St. Dunstan’s Hostel at Regent’s Park provided a place for blinded veterans to rehabilitate and overcome the devastation of losing their sight as a result of their war injuries. In 1915, Sir Arthur Pearson, who was a member of the council of the National Institute for the Blind, responded to the lack of facilities for blinded soldiers by creating a hostel for discharged servicemen who required a supportive environment to assist them to learn to adapt.

St. Dunstan’s fostered a return to life in the face of adversity, a true focus on regaining self-worth and renewed belonging. Pearson himself was an unsighted person and deeply concerned that these veterans would be left to busk or beg in a society not able to accommodate the blind easily within the workforce.14 Massage training was one such occupational program provided at St. Dunstan’s.

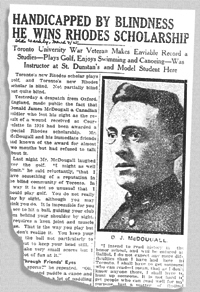

One Blinded Soldier: The Career Of Donald James McDougall

The praise for Sir Arthur Pearson and the specialized work of St. Dunstan’s is evident in Walter Segsworth’s 1920 text titled Retraining Canada’s Disabled Soldiers, and the 1987 account authored by Desmond Norton and Glenn Write titled In Winning the Second Battle, Canadian Veterans and the Return to Civilian Life, 1915-1930.

Both volumes clearly cite the incidence of a remarkable blinded Canadian soldier who would train as a masseur and emerge as an influential and critical link between the British model of massage regulation and the formal regulation of massage in Ontario.

Private Donald James McDougall of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, would arrive at St. Dunstan’s in November of 1916 after his recovery from his injury which the official record describes as … “a bullet T&T (through and through) right side of nose left orbit, Right eye blind, left eye excised.”15

Private Donald James McDougall of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, would arrive at St. Dunstan’s in November of 1916 after his recovery from his injury which the official record describes as … “a bullet T&T (through and through) right side of nose left orbit, Right eye blind, left eye excised.”15

Within the supportive and nurturing environment of the Hostel, Sir Arthur visited McDougall on three occasions during December to talk with him about future occupational training and his depression. Over the course of these personal discussions, McDougall would decide to take up massage.

Training took one year, and on December 10, 1917 he passed his final examinations with the Incorporated Society of Trained Masseurs in second position for all England out of 320 entries. In January of 1918, he took the post as assistant instructor in massage at St. Dunstan’s with hopes to teach at Pearson Hall in Toronto on his return to Ontario. It was modelled after St. Dunstan’s to provide similar training opportunities to all blind Canadian ex-servicemen who had not been through the training program in England.

Lord Ian Fraser’s 1961 book, My Story of St. Dunstan’s, conveys a personal account of McDougall’s success:

In Ontario, McDougall was employed by the Government in a military establishment as an instructor to blind students where his impressive work earned him tremendous renown and respect. He conducted his own massage practice and became somewhat of a local character. In Toronto he was known for his ease with which he travelled the city … an incident where McDougall escorted a drunk home. The man stopped McDougall in need of directions. McDougall took his arm and left off on their way. The drunk stopped him and asked if he saw his father’s motorcar outside the house, and McDougall, in perfect truth, replied that he could not see any car. The drunk, who was concerned that he was unable to drive the vehicle to the garage, was relieved and went on his way, not knowing that his escort was blind.16

Most notably in the transcript from the McDougall file with St. Dunstan’s, Captain Baker reports on January 13, 1925: “The following record of the success of a St. Dunstaner may prove of interest. On his return to Canada he was appointed as Instructor in Massage at the Hart House, Toronto, School of Physiotherapy under Col. Wilson who was in charge of this training department of Military Hospitals in Canada. Remained at Hart House for a period of one year until the summer of 1919 when he was taken on the staff at Pearson Hall and placed in sole charge of the blinded soldiers massage course. He taught this class until July of 1922.”

In an extract from a letter received at St Dunstan’s, sent by McDougall on January 15, 1921, he stated: “Our object now is to obtain protective legislation and so bring the work up to the highest possible standard and have branches in the principal cities in the Dominion.”

He was referring to the organization of a Canadian Society of blind masseurs similar to the Association of Certified Blind Masseurs in England.

During the remainder of 1922 and 1923 he carried on private practice in massage at Pearson Hall Clinic and later in both this Clinic and a private establishment set up in partnership with another blinded soldier and at the same time studied for examinations leading to entrance to the University.17

In the autumn of 1922, he commenced a course at the University of Toaronto leading to a Bachelor of Arts degree. During his first three years he achieved outstanding honours in all courses. By Christmas of 1924 his standing had been so excellent that he was awarded a special Rhodes scholarship covering two years at Oxford. It was the very first occasion that a totally blind student has been awarded such a scholarship.

Donald James McDougall would return to the University of Toronto and enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a professor of history from 1929-1962. In the March 1969 Graduate, a publication of the University, a former student of McDougall remarked, ‘that he knew of no man who could see further into the soul of another man than Donald McDougall.’18

Commentary

The history of massage cannot be told in a sequential progression. There is a need to separate antiquity from the modern, and place social conventions, cultural norms, art, literature, politics and war as markers of the interplay between the practice of massage and its importance in any society along the medical history timeline.

Massage did not remain static. Each era of medical thought and knowledge weaves advancement into the fabric of practice. Manipulations remain relatively unchanged; yet, use, application and evidence to define effects emerge with each new understanding of the structure and mechanisms of the human body.

Throughout, the confusion between massages as therapy and as a venue for prostitution repeats itself. Media continues to portray massage therapists as prostitutes, and often women and men are placed in the position of choosing between their poverty and the demands of their employers in the massage parlours of today. In this example of changes in the 19th century, the regulation of the profession is a mechanism that responded to the demands of public, political and social pressure to eradicate vice and differentiate between illegal and legitimate practice.

War throughout history has always contributed to medical development. WWI demanded a massive workforce

to response to injury. The combined efforts of men from the medical community with women from the Chartered Society had established massage as the superior treatment based in the literature supporting its efficacy in orthopedic rehabilitation.

The British Society of Trained Masseuses in 1894 elevated women toward a greater level of status and recognition for their expertise. Here, physicians and masseuses blended together the necessary information and technology that would imprint on the principles of practice. By the arrival of the War, there was no doubt that

massage was an important therapeutic requirement for rehabilitating wounded soldiers. The surprising secondary development places massage as an occupational career choice for blinded veterans returning home.19

The transfer of knowledge from Europe into the newly formed Dominion of Canada can be viewed through the career of one man.

Donald James McDougall (1893-1978) was trained under the regulatory models of the British system, and his transfer to Hart House in Toronto imprinted the model of training blinded soldiers in occupational massage, which influenced the establishment of the regulation of massage in Ontario.

At the time McDougall returned, women masseuses were working in the orthopedic hospital massage departments across Canada. Just as seen in Britain, women represented the largest numbers of trained masseuses practicing the profession. Toronto of the early 1900s was not without its own controversy over prostitution and legitimate practice. McDougall, and the instructors that dominate the training of massage in 1917 would circumvent the implication of the sex trade and adopt the well-established regulatory model from Britain.

In 1919, massage in Ontario reached regulatory status under the Board of Regents.20 McDougall would be involved in establishing an association to protect the rights of blind masseurs. When the training of the blind masseurs transferred over to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind and

the program closed at Hart House, McDougall was active in the movement toward continued governance under the Drugless Practitioners Act in 1925.

The influx of blind veterans trained as masseurs is an unusual spike in the otherwise female-dominated membership of the profession in Ontario. Between the two world wars, male masseurs dominated private practice, and women generally worked exclusively in the hospital setting.21

After WWII, more options became available for the blind with regard to occupational career choices. The veterans who practiced during the war years eventually retired from practice. The orthopedic rehabilitation hospitals reduced in numbers or closed, and massage departments were replaced with physiotherapy departments. Women employed in these institutions either retired or opened private practice, filling the void left by the men.

McDougall’s legacy is an inspirational case in point. Massage therapy in Ontario became an established therapeutic practice and profession. Literature, combined with scientific rationale, established the language

necessary to communicate the effects of application. The mechanism of regulation supported the foundation for professionalism and social acceptance of practitioners.

Remarkably, out of the tragedy of losing his sight, Donald James McDougall contributed to the vision of establishing the professional recognition and status of massage practitioners in Ontario.

Credits

• This paper is the property of Emily E.S. Cowall Farrell, MT, DHMSA. Reproduction of content in whole or in part requires written permission of the author.

• St. Dunstan’s Hostel, London, The Royal Canadian Military Institute, College of Massage Therapists of Ontario and University of Toronto Archives graciously provided access to primary and secondary source files and photographs.

• Professor Emeritus Pauline Mazumdar, Professor John Crellin, and Professor Emeritus Charles Godfrey assisted in this project as academic advisors.

• The Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology at the University of Toronto supported my research fellowship during this study.

• I would like to acknowledge and thank the individuals who provided external review.

References

- Elizabeth C. Wood, Beard’s Massage: Principles and Techniques 2nd Ed. (Philadelphia: WB Saunders: 1974) Chapter 2: A History of Massage Technique, p. 3-35

- Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, A Medical History of Humanity (New York: WW Norton, 1997) Chapter VIII: Renaissance, Anatomy, p. 183

- Padua: University Medical School Italy (1222), Andreas Vesalius: Renaissance anatomist, lecturer at Padua, De Corporis Fabrica (1543), Vesalian Anatomy.

- Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, A Medical History of Humanity (New York: WW Norton, 1997) Chapter IX: The New Science, Harvey, p. 211-216

- Elizabeth C. Wood, Beard’s Massage: Principles and Techniques 2nd Ed. (Philadelphia: WB Saunders: 1974) Chapter 2: A History of Massage Technique, p. 15-20. Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, A Medical History of Humanity (New York: WW Norton, 1997) Chapter IX: The New Science, Chapter X: The Enlightenment. Jean Barclay, In Good Hands: The History of The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy 1894-1994 (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1994) p. 19-20.

- Jean Barclay, In Good hands: The History of The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy 1894-1994 (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1994) p. 20-23

- Idem, p. 45

- This term was used by physicians who specialized in physical therapy.

- James Beaver Mennell, Massage; Its Principles and Practice (London: J&A Churchill Ltd, 1917)

- College of Massage Therapists of Ontario Archives

- The College Standard, A Mystery Solved: Picturing the Past 7:1 (7) (Toronto: College of Massage Therapists, 2002)

- Report of the Work of the Military Commission Canada May 1917 (Ottawa: J. de Labroquerie Tache printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1917) p. 24-25, 38

- F.W. Coyne, Illustrated Souvenir Edition, Dominion Orthopedic Hospital Christie Street Toronto (Toronto: Dominion Orthopedic Hospital, 1920) p. 35

- Term of reference from St. Dunstan’s website history thumbnail. Viewed 2002.

- St. Dunstan’s Archive Department, London. McDougall file 1916-1978

- Lord Ian Fraser, My Story of St. Dunstan’s (1961) Chapter 11, St. Dunstan’s Overseas, p. 197-198

- St. Dunstan’s Archive Department, London. McDougall file 1916-1978

- University of Toronto Archives: McDougall File A73-0026/264 file 85; President’s Report LE 3-7476, June 3, 1918.

- Walter Segsworth, Retraining Canada’s Disabled Soldiers (Ottawa: J. de Labroquerie Tache printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1920) p. 135, 140

- Sessional Papers, Volume 5 Fourth Session of The Thirteenth Parliament of the Dominion of Canada Session 1920 Volume LVI

- Desmond Morton, Glenn Wright Winning the Second Battle: Canadian Veterans and the Return to Civilian Life 1915-1930 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987) p. 30-31, 92-95,140-141.

Print this page