Features

Management

Operations

Physiology of Fascia

In analysing the efficacy of fascial treatment it becomes imperative to review basic physiology to determine the cause of the restriction in the tissue that is in need of treatment. What is the reason behind a recurring tension? Why, when using traditional techniques on some patients and giving them relief, does the pattern return hours or days later?

September 15, 2009 By Brad McCutcheon

In analysing the efficacy of fascial treatment it becomes imperative to review basic physiology to determine the cause of the restriction in the tissue that is in need of treatment. What is the reason behind a recurring tension? Why, when using traditional techniques on some patients and giving them relief, does the pattern return hours or days later?

In order to answer these questions we must first understand the two primary causes of fascial restrictions; force and neural input. All fascial distortions in the body can be related back to these two mechanisms.

|

|

|

|

Gravity is a force that works against our bodies and fascia must help to control it’s distribution. When our bodies absorb force in the way they were designed to, we see minimal adaptation and minimal change.

When the slightest deviation of gravity occurs, from a repetitive motion for example, fibroblasts are chemically activated to produce more tropocollagen (a small linear molecule consisting of three strands of procollagen formed from Leusine, Glysine and Tyrosine) that is then formed into collagen in the ground substance.

If the force that activated the entire process was great enough to require collagen support then this new collagen is laid down to absorb the force the next time it travels through the tissue. In English this translates to; a small force will create small fibres of support and a large force will

create larger fibres.

This philosophy outlined briefly above supports what is known as Wolff’s Law. Although you may have learned this in regards to bone and calcium formation, do not forget that bone is a connective tissue and that it is formed in the same way that fascia is. The only

difference is that after it is formed sedimentation occurs that creates calcium phosphate salt deposits on the connective tissue creating a firmer more ridged tissue. (refer to a physiology text for more detail)

The second of the two causes of fascial distortions is neural input. Think back to neuro-physiology and a boring lecture on nerve endings. Depending on what text your instructor used there were between nine and 12 different nerve endings some contained in capsules, encapsulated, and some without capsules, unencapsulated1. (Illustration opposite page)

Did you ever stop to think what the capsules are made of? Capsules are connective tissue, and all of these nerve endings are found inside or between layers of connective tissue.

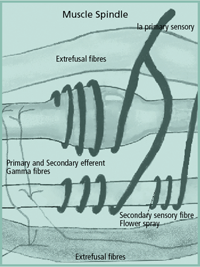

The only exception to this is the muscle spindle which has a fusal capsule (fascia) that separates the intrafusal from the extrafusal fibres. The muscle spindle is an exception because it is found in muscle tissue but it is still embedded in the muscle’s connective tissue.

Neural input, according to Dr. Keith A Buzzell D.O. and Dr. Irvin M Korr Ph.D., is the data from all of these nerve endings, the positions of the viscera, the spinal nerve roots, and the spinal cord2. (Please note that many authors have come to these conclusions, the choice of references is by preference of the author only). To bring this into the realm of massage let me use an example, if a patient presents to your clinic with a repetitive strain injury to their right elbow, the neural input from the nociceptors in the right arm will be increased, (causing a neural impulse to travel to the brain) the compression on the pacinian corpuscles when they contract the right hand will be added to this impulse and will further cause the nociceptors to fire, (explained completely in Caillet)3 the muscle spindles will adapt to help change the tension on the muscle thus reducing the tension on the tissue and reducing nociceptive input.

|

|

|

|

This will then cause the fascia to change it’s shape to adapt to the new forces that now passes through the tissue. Local treatment of the musculature of the forearm using compressive type or friction type techniques will decrease the nociceptive firing and give some pain relief.

However when the patient stands against gravity and the fascia of the elbow flexors pull tight against the elbow, the muscle spindle will fire again restoring the neurological loop of the nociceptive input to the spinal cord and the pattern will return. (translated roughly from Mitchell D.O.)4 This sounds very complicated in it’s language, however it is quite simple if you remember that fascial distortions can be caused by neurological input or by force or a combination of both.

Having bored half of the readers by now with neuro-physiology I think it would be pertinent to change gears and explain the physiology of fascial treatment. Fascia while maintaining it’s awe in the manual therapy field is really quite basic to treat.

While there are many catch words circulating around our profession, if you break them down to what they are doing, they can be categorized into 3 basic techniques;

1. The direct correction: using a stretch you attempt to lengthen a connective tissue. If you do this lengthening before the firing of the nervous system you will, cause a thixotropic change in the ground substance, softening of cross bridges and eventually a sliding of the collagen fibres in relation to one another, causing a lengthening of the tissue in general.

If you stretch and cause the nervous system to fire, you are actively stretching and must wait for a plastic change, this in many authors opinion including mine is not fascial release and will not give permanent change.

Examples of direct techniques include myofascial release, fascial unwinding and 3 plane fascial release and any derivatives of the above.

Just to confuse matters, if you take a tissue to a direct correction and then use the nervous system to attain the release, you are still doing a direct correction, as is the case with Muscle Energy.

2. The oscillation – using a stretch like technique but using the force of an oscillation to cause the tissue to release. Variations of this technique traverse into massage all the time. Vibrations, shaking can both be done at the fascial level. Although this technique uses the same physiology as the direct correction, adding the oscillation can include the nervous system into the correction, and therefore it is given its own name.

3. The indirect correction – the exact opposite to a direct technique, in this category the tissue is taken to it’s ease of tension and a neurological release is attained. By shortening all tensions in the tissue, the nervous system stops firing.

Given this opportunity to manipulate the physiology a practitioner will then wait for a resetting of the nervous system (the muscle spindle and GTO specifically) and then restore normal tissue length afterwards.

Examples of this technique are many, however the most important of which is the Strain-Counterstrain technique first described by Dr. Jones D.O. Probably the most stolen and manipulated (pardon the pun) of the fascial techniques.

I hope that this review and description of techniques helps give you a better understanding of what you are doing. Remember the first rule of therapy is “DO NO HARM.”

References

- Arthur C Guyton M.D., “Textbook of Medical Physiology”, Seventh Edition, W.B. Saunders Company Philadelphia 1986

- 2. Dr. Irvin M Korr, Dr. Keith A Buzzell, “The physiological basia of Osteopathic Medicine,” Insight Publishing, 1982 Williston Park NY

- Rene Caillett, M.D., “Soft Tissue Pain and Disability”F.A. Davis Company, Philadelphia, 1983.

- Dr. Fred Mitchell Jr. Do. FAAO. FCA, “The Muscle Energy Manual” Volume 1 MET Press, East Lansing Michigan

- Dr. Irvin M Korr, “The physiological basic of Osteopathic Medicine,” Insight Publishing, 1982 Williston Park NY

- Serge Paoletti, “Les Fascias,” Sully Editions, Vance Cedex, France, 1994

- Eyal Lederman, “Fundamentals of Manual Therapy,” Churchill Livingstone, New York 1997

- Brad McCutcheon, “Fascial Integration an fascial assessment and treatment methodology for massage therapists,” JSTM Spring, Summer, Winter 2000.

Brad McCutcheon MT, CNC, SMT(c). NCMT, Osteopath (thesis candidate)

Print this page