Features

Practice

Patient Care

Rethinking the pain scale

How much do pain assessments need to evolve, on a scale from 1 to 10?

June 21, 2021 By Mike Straus

© kritchanut / Adobe Stock

© kritchanut / Adobe Stock Assessing patient pain is an essential aspect of the intake process. Pain is often what prompts patients to seek care, and measuring that pain over time is vital to determining whether treatments are working. Pain can be a valuable source of information for clinicians, often making it possible to identify problem areas and develop solutions.

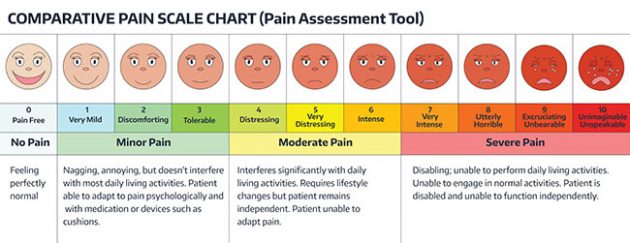

But while pain is an important symptom full of information about the underlying cause, the standard instruments of pain measurement extract very little of that information. The typical 1-10 scale that appears on posters and websites has little bearing on what the pain means from a diagnostic perspective, and even less bearing on the patient’s subjective experience of pain.

Ken Craig, OC, PhD, LLD (Hon), is a clinical psychologist, a former Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Pain Society journal Pain & Research Management, a former Chair of the UBC Behavioural Research Ethics Board, and an Officer of the Order of Canada. Craig is a researcher who specializes in pain measurement methods, social influences on pain perception, and biases in judgments of pain in care settings.

Craig says that pain scales are long overdue for innovation due to the problems associated with the most common forms of pain assessment:

“For the most part, pain measurement has been pretty static,” Craig says. “Most clinicians and researchers adhere to the principle that self-report is the gold standard, and while self-report is valuable and necessary, I think clinicians need to pay more attention to non-verbal expression.”

© sunshine_art / Adobe Stock

Numerical scales don’t tell the whole story

The traditional 1-10 scale is limited in a significant way: It does a poor job of capturing the experience of pain.

Craig explains that patients dislike the 1-10 scale because it reduces incredibly important thoughts and feelings to a simple numerical index. The human experience of pain is much more complicated than simple numbers can describe, Craig says, and integrating thoughts, feelings, and sensory experiences into a single number can obscure a lot of valuable information.

“People have all kinds of thoughts, feelings, and somatosensory experiences going on all the time,” Craig says. “In order to communicate with someone, I need to understand what they think and want. Pain is a subjective experience. Most definitions of pain describe it as a sensory experience with emotional overtones, but pain is much more complex than that. It has cognitive and social features, and if you’re sensitive to those other characteristics, you can understand it better and deal with it more effectively.”

Craig also notes that patients themselves can introduce confounds into pain measurement when the 1-10 scale is in play. For instance, it’s not uncommon for chronic pain patients to claim that their pain is at a 12 on a scale of 1 to 10. In this case, he says, the patient isn’t trying to communicate the severity of their pain, but rather, their level of subjective distress and desperation for care. Other chronic pain sufferers, Craig says, will under-report their pain level on self-reports out of stoicism.

Finally, Craig says that numerical scales are one-dimensional. The 1-10 scale only captures pain intensity. It doesn’t capture the other nuances of pain like duration, quality/nature, suffering/emotional distress, or impact on the patient’s quality of life.

Jen Fleming, RMT, is a massage therapist at MMD Chiropractic Health Centre in West Hamilton, ON. Fleming specializes in trauma-informed care, an approach to care that considers the role of trauma in injury.

Fleming says that while the numerical 1-10 scale is the most common pain scale, many patients simply don’t find it useful. The patient’s point of reference will always influence the answer, she says, which makes the scale problematic.

“A lot of people, especially those who live with chronic pain, don’t find numerical ratings useful. People who live their entire lives at what, for the rest of us, would be a 7, find 7 to be their new level of tolerable pain. So that 7 rating isn’t useful anymore. Similarly, people who have had extremely painful acute experiences may say a severe pain is tolerable because they have a different form of reference.”

Fleming says that she doesn’t use pain scales when treating patients who have persistent pain or catastrophic injuries. Instead, she says, her approach likens pain to the volume dial on a stereo. Everyone can relate to what it feels like when a stereo is too loud, she says, which is why this analogy is useful for communicating pain levels:

“It’s funny; people who relate to the 1-10 scale will stick with it, but a lot of patients who have struggled to articulate their pain will have a much easier time communicating it when we switch to the stereo metaphor.”

It quickly becomes apparent with practice that the scale isn’t as objective as many would

like to believe. © 9nong / Adobe Stock

Patient-led innovations in pain assessment

Much of the recent activity in the development of better pain scales has come from a surprising source: Pain patients. Patients themselves are creating more objective and informative pain scales, including multidimensional pain scales that capture more facets of the experience of pain than just intensity. For instance, Houston, Texas-based health blogger and chronic pain sufferer Liza Zoellick notes that standard 1-10 scales are inadequate for communicating the nuances of pain.

Zoellick, who has fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis, wrote in a February 2019 article for the National Pain Report that pain scales are subjective by nature. She explains that “when presented with (a standard 1-10 scale), it feels like you are trying to fit my pain into your version of what you think it should be. So if I say I am at an 8, and I am not panting out my words because of the pain, then what?”

Another unlikely source for innovations in pain scales is the world of comedy. In 2010, notable comedy blogger Allie Brosh wrote a blog article about a recent trip to the emergency room at her local hospital in which she pinpointed the shortcomings of the Wong-Baker scale. In her article, Brosh proposed an alternate scale that ranges from zero to “Too Serious For Numbers.” On the Brosh Scale, a 1 means “I’m unsure whether I’m experiencing pain, or itching, or maybe I just have a bad taste in my mouth,” while a 10 means “I am actively being mauled by a bear.”

While this scale was originally intended as comedy, researchers contend that the Brosh Scale offers more diagnostic value than scales that are currently in use in actual medical settings. Kenneth D. Royal, PhD, an Associate Professor at North Carolina State University, wrote in a 2013 paper for the Institute for Objective Measurement that the Brosh Scale effectively captures the nuances of pain like intensity, duration, and quality. In this respect, Royal argues, the Brosh Scale is a more effective means of measurement than the Wong-Baker Scale and other scales like it.

The Brosh scale also offers the advantage of patient-centric language. Rather than compressing a complex human experience into a single-digit number, the Brosh scale mirrors the language that patients use when describing or experiencing pain (including the use of expletives).

Patient-created scales meet patients where they are, Fleming says, which helps to validate patient experiences:

“I always tell my patients, ‘I can’t know what it’s like to be in your body. The more ways you can find to tell me what it’s like to be in your body, the better I can understand.’ I’ve heard a colleague describe the pain scale she uses with children, and it’s brilliant. The scale is based on colours. The child’s favourite colour represents a pain-free day. Then, the child picks a colour they don’t like, and that represents a bad pain day.”

Non-numerical scales may offer patients a better means of communicating diagnostically relevant information. Craig says that patients don’t typically like the numerical scale because it tells them to reduce incredibly important thoughts and feelings down to a number, which can obscure diagnostically relevant phenomena. He highlights the distinction between nomothetic and idiographic scales.

“(Nomothetic) scales that have been developed by clinicians tend to be standardized and have common characteristics,” he says. “The advantage of a broadly-applied scale is that you can compare individuals with each other. Idiographic scales are more likely to be highly sensitive to the nuances of the individual’s experience.”

Both scales, Craig notes, have advantages and disadvantages. Nomothetic scales, which are designed to be objective enough that they can be reliably applied across a broad range of individuals, allow for comparisons between individuals and groups. However, these scales fail to capture many of the subtleties of personal experience. In contrast, idiographic scales are developed for specific individuals, either by the individuals themselves or by clinicians. An idiographic scale will allow for more effective measurement of the subjective experience of pain at an individual level, but will make comparisons across individuals difficult.

Fleming says that future pain scales need to move away from the numerical VAS and toward a more flexible method that allows patients more autonomy over the language they use to describe pain. Her ideal pain scale, she says, would leave room for patients to talk about pain instead of burdening patients with a tool that only makes sense to practitioners:

“Some people can have a lot of difficulty describing what their pain experience is like. Even if they describe it well, I may not understand. Some patients may use the word ‘discomfort’ instead of ‘pain,’ so trying to suss out where the line between discomfort and pain is can be challenging. ”

While classic descriptors like “shooting,” “burning,” and “tingling” can be useful to determine the nature and origin of pain, Fleming’s stereo metaphor is the kind of pain measurement tool that can capture the subjective experience of pain. It’s these kinds of tools – assessments that quantify the subjective experience of pain on quality of life measures – that are currently most useful.

An AI-derived pain scale is something that researchers in bioinformatics and computer science have been working toward for several years, and researchers at MIT’s Affective Computing group are getting close to developing a working pain measurement system based on artificial intelligence. This system determines pain levels by AI analysis of brain activity through a portable neuroimager. Through machine learning, the researchers were able to achieve 87 percent accuracy with the apparatus.

The best pain scales, at least for now, are the scales that measure quality of life.

Mike Straus is a freelance writer based in Kelowna, British Columbia. He has written on health and science topics for Canadian Chiropractor/Massage Therapy Canada, Nutritional Outlook, Grow Opportunity, and StarTrek.com.

This story was originally published in the Spring 2020 edition of Massage Therapy Canada.

Print this page