Features

Patient Care

Practice

Robust records: 5 principles to punch-up your charting

Charting is an everyday aspect of your practice – and a requirement for a regulated health profession. In my reviews of practitioner records, there has been great variability in charting comprehensiveness and style.

January 7, 2019 By Don Quinn Dillon

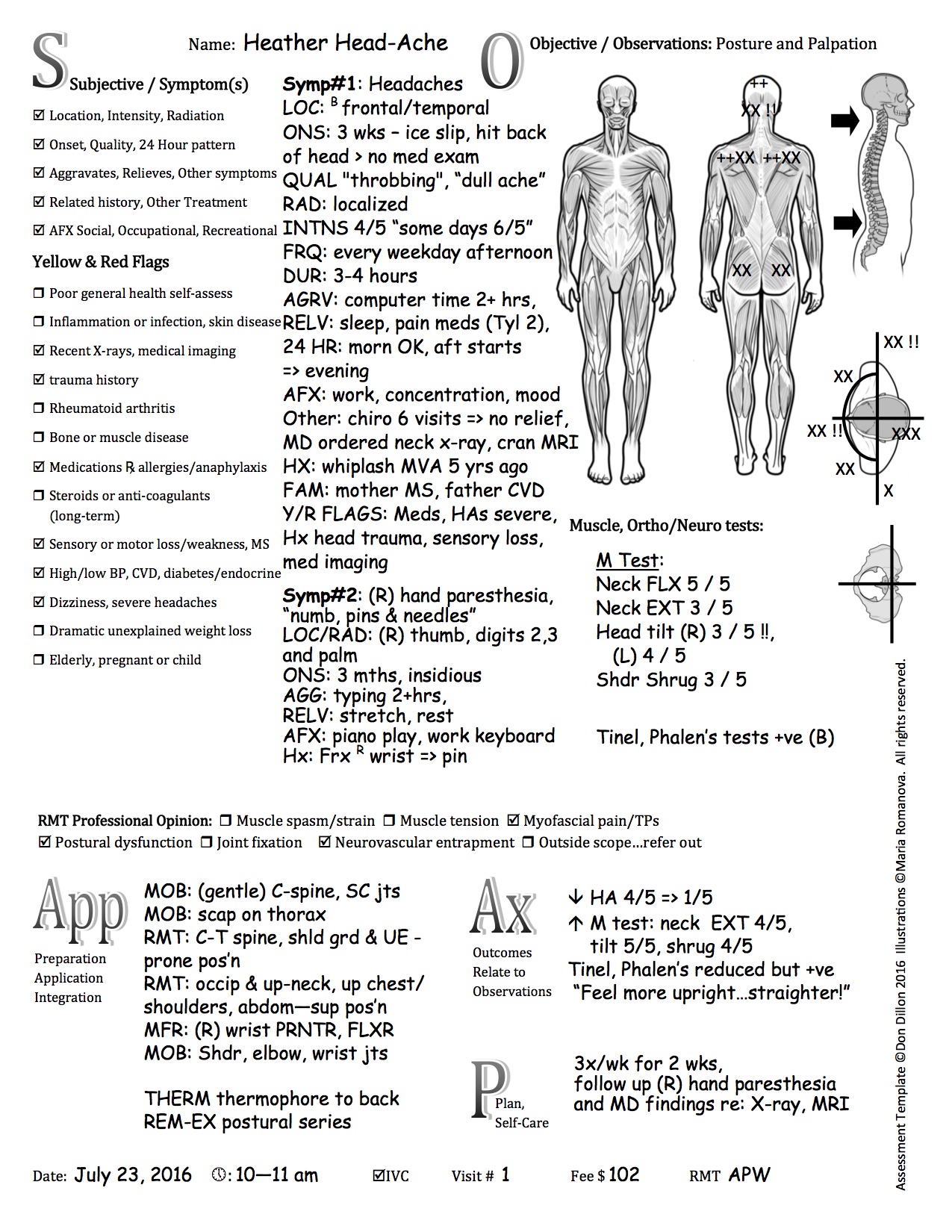

Assessments and meaningful outcome measures may be absent, and risk of harm is ineffectually screened for. Charting may be perceived as “something I have to do” rather than a real opportunity to effectively capture the person’s health status and symptom picture. The charting process helps uncover otherwise overlooked symptoms that impact quality of life and focus the practitioner’s treatment plan.

Whatever your current charting method, injecting these five principles into your daily records can help you produce meaningful, measurable and more robust records while reducing risk of harm to the people you care for.

Reduce risk of harm

A primary reason for conducting a case history is to reduce risk of harm – to ensure your interventions will not ultimately worsen the person’s condition or health status. The challenge is to keep risk factors top-of-mind as you proceed through care. Building checkpoints into your case history help screen for precautions (“yellow flags”) and preclusions (“red flags”). In Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment by Petty and Moore (Churchill Livingstone), the authors outline a number of conditions that are cause for pause. These include a report of general poor health, fatigue or rapid weight loss, recent diagnostic tests, a history of rheumatoid arthritis, long-term use of medications (particularly steroids and anti-coagulants), neurological symptoms or dizziness. In my case history, I add signs of inflammation or infection, history of trauma, high/low blood pressure, sensory or motor loss, and consideration if the person is elderly, pregnant, or a child.

Once I provided care to a person on a type of blood-thinning medication. Our sessions had yielded positive outcomes generally, but on one occasion I deepened my pressure. This caused the person to suffer with pain and stiffness for several days following. I had lost site of the original yellow flag. Now I incorporate a check-box list of yellow/red flags on my assessment template to ensure I ask specific questions during a case history, and that these concerns garner my attention on each visit.

We can’t assume that a person already in a physician’s care has been sufficiently cleared for our interventions. Martha Costello, DC, warns in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapy (April 1998), “Bodyworkers should be cautioned. Often, when a patient has seen a medical professional prior to consultation with the bodyworker, it is assumed that all organic or pathological causes for symptoms have been ruled out. Unfortunately, this often is not the case, as the prior medical examination may have been cursory, and a thorough history may not have been conducted. It is not uncommon for even a review-of-symptoms questionnaire to have been extremely brief, painting a very incomplete picture of the patient’s current and past health history.”

Draw a professional conclusion

Practitioners go through the trouble of gathering case history information and conducting various assessments, yet may leave their conclusions unformed. A provision in Ontario’s Regulated Health Professions Act lists forming a diagnosis as a protected act, privileged to a small group of gatekeeper health disciplines. RMTs may exclaim, “we can’t diagnose.” It’s true we don’t retain the privilege of conveying a diagnosis, however this doesn’t preclude RMTs from dovetailing case history information with assessment findings to come to a conclusion…a professional opinion. Without a professional opinion, it’s impossible to effectively address all the symptoms and resultant sequelae the person on your table presents with.

Dr. Hans Kraus, MD (1905-1996) physician and physical therapist, provided us with a series of muscle dysfunctions – muscle tension, muscle spasm/strain, myofascial pain/trigger points and muscle deficiency (a postural/muscle imbalance). These dysfunctions can act as a starting point for dialogue and debate within the profession to get more comfortable in critically examining the case before us, and drawing a conclusion (our professional opinion).

State the big picture

The design of your assessment template should allow you to record all pertinent case history information – coupled with additional information gathered, and screening for precautions and preclusions – along with your assessment of functional (range of motion, posture, muscle strength and length) and subjective/life quality (pain perception, limits in activities of daily living, effect to sleep, recreation, occupation or social) aspects. You’ll need sufficient room to record your professional opinion, massage applications, post-session outcomes and a treatment plan, along with particulars of date, time/duration, consent provided, practitioner’s signature.

Your assessment template should give a complete picture of the person’s complaints, limitations and health status at this moment in time. This comprehensive picture allows ongoing notes to be concise and targeted, while serving as an official record should your records be audited. It’s also a helpful share document (with the person’s consent) back to their primary health practitioner to update the practitioner on your findings, but also to demonstrate the breadth of your scope. You may even gain a few referrals from this practice.

Build a treatment scaffold

I’ve had the opportunity – both in reviewing charting of RMTs facing disciplinary action, to records submitted in Designated Assessment Centres I’ve been contracted in – to view records in all shapes and sizes. Sometimes I’ve seen only “FBM”, full-body massage. Check-box/multiple choice designs (checking body regions, strokes applied, modalities used) don’t correlate well and fail to properly transcript what actually happened in the session.

While RMTs are not the only profession who suffer from a paucity of detail in our charting, we can improve on how we record the therapy we’ve provided. I recommend building a scaffold – shaping your treatment record by listing body position, methods and modalities applied, body regions treated, and specific areas of concentration. By laying out these variables, you will be able to look back five years on the record and know precisely what treatment you applied and the outcome of that session.

Measure meaningfully

It’s important to regularly incorporate recognized functional assessments (range of motion, muscle length/strength) along with exploring quality of life measures like numeric pain scale, impacts to sleep, mood, and recreation/occupation/socialization. Massage therapists benefit from using measures meaningful to them, contribute to better public health, and progress the function and quality of life of their clients/patients.

Vernacular for conveying massage therapist findings was stultified when medicine turned its attention to organ systems exclusive of the movement system comprised of muscle, bone and connective tissue. The RMT profession could benefit from an exploration of terms like myalgia, myositis, myogelosis, and other terms assigning language to what we find under our hands. Antoine Laurent Lavoisier stated, “As ideas are preserved and communicated by means of words, it necessarily follows that we cannot improve the language of any science without at the same time improving the science itself. Neither can we, on the other hand, improve a science without improving the language or nomenclature which belongs to it.”

Donald Quinn Dillon, RMT is author of Charting Skills for Massage Therapists, a self-study program. Find him at DonDillon-RMT.com

Print this page