Features

Practice

Technique

A Complementary Approach To Addressing Common Golf Injuries

Odds are that you’ve assessed and treated a golfer in the past few months. Golfers tend to be similar to the rest of the population – they would love a quick fix for both their game and health challenge.

September 9, 2009 By mark elliott rmt

Odds are that you’ve assessed and treated a golfer in the past few months. Golfers tend to be similar to the rest of the population – they would love a quick fix for both their game and health challenge.

One of the key features of golf in the future is the need for the work of the instructor and medical professional to complement each other. Poor swing mechanics may hasten injury, while altered soft tissue and joint mechanics will lead to a poor swing! Instead of engaging in this chicken vs. egg debate, let’s allow both professions to enhance the golfer’s potential. In most cases, treatment and rehabilitation of an injury may assist their golf game while correction of swing flaws and improved kinematic sequencing of the golf swing can lead to better health!

I’ve picked three common types of injury to discuss, with brief explanations of the types of movements normally employed to sustain the injury.

|

|

| Figure 1 Advertisement

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2

|

|

Low Back

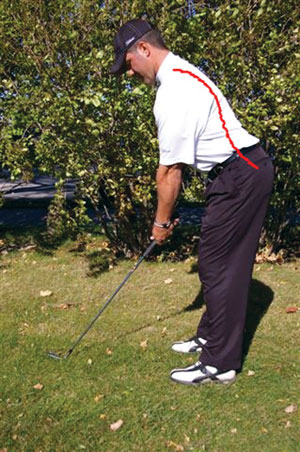

Statistically, the lumbar region is the most frequently injured area for amateur golfers (and in second place for the professionals!). What I see most commonly at the Practice Centre is the “S” posture (figure 1). It is recognized by the Titleist Performance Institute (TPI) as the number one cause of low back pain among golfers.

You will recognize this fault as hyperlordosis. This position is often assumed at the address position of the golf swing and leads to inhibition of the abdominal and gluteal muscles. Unfortunately the golfer may have been instructed to “stick their butt out” as part of their golf posture. Hyperlordosis satisfies this request and leads to poor swings and back pain.

What can the RMT offer this golfer? Hyperlordosis treatment may assist in pain reduction, but I believe that education of the golfer is paramount. It must be stressed that a neutral pelvis (figure 2) is mandatory for a healthy low back and more consistency while striking the golf ball. After demonstrating what neutral pelvis feels like (or looks like if you have access to a mirror), have the golfer hinge from their hips and assume their golf address position while maintaining a neutral, stable posture. Voila! What happens? It appears as if the gluteals “stick out” but with a much cleaner appearance through the thoraco-lumbar spinal region.

Obviously this requires decent core abdominal strength and control, which is always good remedial exercise for the golfer. I have found that golfers often suffer from *Lower Crossed Syndrome (LCS) – a grouping of tight hip flexors and lumbar spine, combined with weak abdominals and gluteals.

What Vladamir Janda1 documented still holds true today – prolonged static postures (such as sitting at the computer writing articles) will lead to muscle imbalance and predictable movement patterns. In this case of LCS, the hip flexors become short and tight, leading to inhibition of the gluteals. The human body will then recruit the low back musculature and hamstrings for assistance in performing hip extension. A tell-tale sign of LCS in your clinic? A flat butt, often combined with a protruding abdomen. It is also easy to spot a golfer who has a lower crossed syndrome by observing their set-up posture from down-the-line. If you look at their lower back it has an excessive swayback or curvature creating the “S-posture.”

Strange but true: Relatively tall, slender players are more likely to experience low back pain than relatively short heavy golfers!2

• A future article will deal with both LCS and its superior cousin, Upper Crossed Syndrome.

|

|

| Figure 3 |

Tennis Elbow

Wait a minute – shouldn’t this be golfer’s elbow? TPI has found that lateral epicondylitis outweighs medial epicondylitis by an over five to one ratio. Golfers tend to experience Tennis Elbow on the lead arm (left arm for a right handed golfer), and Golfer’s Elbow on the trail arm. Often, it is the golfer who attempts to “scoop” the ball airborne at impact, followed by a “chicken wing” (figure 3) follow through that is affected.

Golf specific bio-mechanics and swing faults are best resolved by consulting with a professional golf instructor.

For the therapist, I believe it is important to address three areas when treating any epicondylitis injury.

- Instruct the golfer to avoid sleeping on their arm or elevate the arm above the head at night. I believe this is often the reason epicondylitis is such a frustratingly chronic injury to treat. All of the therapist’s and patient’s hard work is undone in the bedroom!

- Grip pressure on the golf club should be 4/10 maximum. As Sam Snead, winner of 82 PGA tournaments once said, “If everyone gripped their knife and fork like the golf club we would all starve.” A golf club is like any other tool that your patients use in their activities of daily living. If gripped too tightly, the soft tissue will become inflamed.

- Don’t ignore the strength component of remedial exercise!

|

|

| Figure 4 |

Shouldering The Load

Two of the most common golfing shoulder injuries are rotator cuff tendonitis/trigger points and impingement syndromes. Electomyograph (EMG) of the shoulder during the golf swing has shown:

- Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus were relatively minimally active throughout the golf swing, and equally involved bilaterally.

- Subscapularis was the most active rotator cuff muscle, especially on the dominant (right for right-handed golfers) side.3

The external rotators undergo a great deal of eccentric contraction stress with an upper body dominant player. These, upper body dominant, golfers will most likely be affected by the dreaded “slice” (applying clockwise spin on the ball resulting in a left to right shot pattern for right-handers). Ideally, a golfer would employ the lower body to initiate the forward swing. Unfortunately those afflicted with rotator cuff injuries are often those that over swing with their arms. This is a “hit and hope” scenario whereby an extremely aggressive arm swing is used in the attempt to hit the ball greater distance. This adds strokes and is deleterious to the rotator cuff.

Traditional treatment for tendonitis and trigger points should be employed according to the golfer’s clinical presentation. It is imperative that the rotator cuff is strengthened for long-term health and golfing success. Winter offers a brilliant opportunity to accomplish this, with emphasis on sub-maximal (40 per cent is what I recommend) resistance and high repetitions (25 reps is a terrific goal).

Concerning impingement syndromes, the lead arm (left for a right-hander) performs horizontal adduction, pronation and flexion (figure 4) during the backswing. Players who excessively pronate during the backswing will often present with impingement. They may experience this sensation at the top of the backswing as Supraspinatus gets pressed between the humerus and bottom of the acromion/coracoacromial arch. This condition, given time and repetition, can lead to muscle strain, tears, tendonitis and bursitis.

Following their treatment, send the patient to a golf lesson – it’s only a matter of time before the over-pronation leads to a physical breakdown.

One additional point to remember is that most shoulder injuries may be avoided by maintaining a healthy thoracic spine and scapulo-thoracic joint. With normal pain-free movement of these areas the gleno-humeral complex is not required to shoulder the load! Take care, and remember, in life and in golf, play the ball as it lies!

ABOUT MARK ELLIOTT

• Mark Elliott is a Level III golf teaching

professional licensed through the Canadian Golf Teacher’s Federation and the United States Golf Teacher’s Federation.

• He is a Certified Golf Fitness Instructor and a certified Medical Professional of the Titleist Performance Institute (www.mytpi.com).

• Mark has maintained a Massage Therapy practice in London, Ontario since 1996. He can be reached with questions or concerns at 519-495-3977 or mkelliott@rogers.com.

References:

1. Janda V. Muscle spasm – a proposed procedure for differential diagnosis. Manual Medicine, 1991: 6136-6139.

2. Evans, Refshauge, Adams and Allprandi. Physical Therapy in Sport 6 2005: 122-130.

3. Pink M, Jobe FW and Perry J. Electromyographic analysis of the shoulder during the golf swing. American Journal of Sports Medicine 1990: 18(2): 137-140.

Print this page