Features

Practice

Technique

More Than A Pain In The Buttocks

October 1, 2009 By Fiona Rattray RMT & Linda Ludwig RMT

Definition & Symptoms

A client may describe pain in the buttock and back of the thigh as sciatica. For therapists, however, it’s not a specific term, since it doesn’t indicate the source of the pain or which structures to treat.

The sciatic nerve roots could be squeezed by a lumbar disc protrusion, or the nerve could be compressed somewhere along its pathway, such as at the sciatic foramen; or facet joints in the spine or the sacroiliac (SI) joint could refer pain.

The sciatic nerve roots could be squeezed by a lumbar disc protrusion, or the nerve could be compressed somewhere along its pathway, such as at the sciatic foramen; or facet joints in the spine or the sacroiliac (SI) joint could refer pain.

Health history questions and assessment, covered elsewhere in this magazine, will help the therapist differentiate the cause and determine a treatment plan.

This article focuses on piriformis syndrome, or compression of the sciatic nerve by piriformis muscle, resulting in leg pain and other symptoms. Two other components that contribute to the syndrome are trigger points in piriformis and SI joint dysfunction.

- As with other entrapment syndromes, an increase in the size of the contents passing through an available space contributes to compression. Normal contraction of piriformis will increase its girth. Therefore, if piriformis fills the space snugly, any contraction or shortening of the muscle will compress the nerve.

- Trigger points refer pain and other symptoms such as paresthesia locally and some distance from their location. They can be made active by overuse. Trigger points occur in taut bands of muscle fibre that cause the affected muscle to shorten. As it shortens, it increases in girth, further compressing the nerve. Because of this, both trigger point pain and nerve compression pain may be present.

- Finally, because of the attachment and action of piriformis, the SI joint can become involved, creating pain and dysfunction. Increased tension in piriformis leads to displacement of the SI joint, which can perpetuate trigger points in the muscle.

Symptoms of piriformis syndrome are usually one-sided. One researcher noted the syndrome is “frequently characterized by … bizarre symptoms that may seem unrelated.” These include pain and paresthesia in the buttock, posterior thigh, and sometimes down to the sole of the foot. There may occasionally be pain on defecation. Swelling may occur in the affected leg. If the compression is severe, there may be the loss of proprioception and/or muscle strength in the lower leg. If the pudendal nerve is affected, sexual dysfunction may be present.1

Prolonged sitting or standing may be painful and difficult; the person may shift position frequently, or have trouble crossing the legs. Rising from sitting to standing makes symptoms worse. Any activity that involves hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation such as kneeling or squatting also increases the pain.

How Common is Piriformis Syndrome?

Medical opinion is divided as to whether it is rare or common. A quick Google of the term will lead you to some medical websites placing the syndrome as rare or non-existent, yet other medical, osteopathic and chiropractic sites describe it as something likely seen in practice. In one documented instance, piriformis syndrome was more common than disc-related lesions.2 Even sources suggesting that this syndrome is uncommon agree that the most likely cause of entrapment is the nerve passing through a taut piriformis muscle.3

What Causes Piriformis Syndrome?

Overuse of Piriformis

- Examples are repeated bending and lifting; forceful rotation with the weight on one leg; squatting while putting down a heavy object; jogging or using step machines.

Postural Concerns

- Pronation, or flat-footedness, increases internal rotation of the lower leg and thigh, overworking piriformis as it attempts to control this rotation.

- Short hip flexor muscles create an increased anterior pelvic tilt. The gluteal muscles tighten in an attempt to stabilize the pelvis, compressing the sciatic nerve against the bone. This situation can occur in the third trimester of pregnancy with the shift in the woman’s centre of gravity and increased external rotation of the hip to accommodate the expanding abdomen.

Shortening Activation

- If the muscle is placed in a shortened position for a prolonged time, piriformis becomes hypertonic and can compress the nerve. Trigger points can also become active by prolonged muscle shortening. Examples of this position are sitting with your knees abducted, often with ankles crossed; sitting on one foot or with a wallet in a back pocket; gardening with all the kneeling and bending; and driving a car for long periods with your foot on the accelerator.

Trauma

- These include: a direct blow, like a fall on the buttocks; indirect injuries such as slipping on ice and catching yourself before you fall; or motor vehicle accidents, especially if the impact was to the side of the vehicle. Direct trauma leads to inflammation and muscle spasm, eventually resulting in microscopic scar tissue and active trigger points. Indirect trauma overloads the muscle, also producing trigger points and spasm.

A Bit of Anatomy

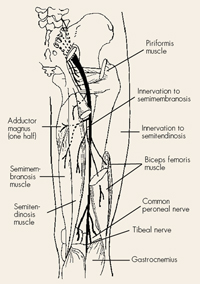

The sciatic nerve, the largest and longest of the peripheral nerves, is actually comprised of two nerves (the tibial and peroneal divisions), which travel together down the leg to the knee. The sciatic nerve supplies motor function to the hamstrings and muscles of the lower leg and foot and it it also gives sensory supply to the posterior thigh, and most of the lower leg and foot (Figure 1).

The nerve arises from the sacral plexus on the anterior surface of the sacrum – nerve roots L4 to S3. On its way to the posterior part of the pelvis, it passes through the sciatic foramen, an opening bordered by the hard bony rim of the sciatic notch of the ilium and the inflexible sacrotuberous ligament.

The sciatic nerve shares the foramen with piriformis muscle, usually passing anterior to piriformis, then runs down the leg, posterior to the femur. At the knee, it splits into its two components: the tibial nerve (supplying the posterior lower leg and foot) and the peroneal nerve (supplying the anterior lower leg and foot).

Piriformis attaches to the anterior surface of the sacrum (S1 to S4) and runs almost horizontally to the greater trochanter of the femur (Figure 2). The name refers to its appearance, pirum meaning pear and forma meaning shape. The broader portion of the muscle emerges from the sciatic foramen and it narrows at the greater trochanter. Covered by gluteus maximus, piriformis can vary in size from person to person: usually it’s bulky, filling the sciatic notch. In a minority of cases, one or both of the divisions of the sciatic nerve penetrates piriformis muscle, creating another entrapment site.

Even with the usual anatomic presentation, a thicker or tighter piriformis can compress the sciatic nerve against the rim of the sciatic foramen.

Piriformis’ action depends on the position of the hip joint and whether the leg is weight-bearing or not. This concept is important when determining a stretch for piriformis or choosing the antagonists to treat.

In the non-weight-bearing leg, when the hip is in a neutral position or in extension, piriformis externally rotates the femur; when the hip is flexed to 90 degrees, the muscle horizontally abducts the femur; and when the hip is fully flexed, piriformis internally rotates the femur.

In addition, during weight-bearing activities such as running or the stance phase of walking, the muscle controls rapid internal rotation of the hip.

An Observation

In the standing or prone client, you may notice that the client’s sacral sulcus (a depression just medial to the PSIS) is deeper on the side of the affected piriformis. Since this muscle attaches anteriorly on the sacrum, a short, tight piriformis on the right side will cause oblique sacral rotation to the left, with the sacral base more anterior on the right side relative to the ilium.

- In other words, using your hand to represent the sacrum, hold your right hand up in front of you, palm facing away, fingers together. Your fingertips represent the sacral base, and the heel of your hand represents the sacral apex and coccyx. The right piriformis attaches to the palmar surface of the base of your little finger. When this muscles is tight, it tips the sacrum: your hand rotates so the little finger goes slightly down to the right and away from you (while your thumb, representing the left side of the sacrum, moves up and towards you).

Pace Abduction Test

Dr. Pace, the author of an early paper on Piriformis Syndrome, developed a test for this condition. The person being tested is seated. The therapist places her hands on the lateral knees, applying some resistance, and asks the person to push the knees apart. Weakness and pain will be noticed on the affected side as the person attempts abduction.

What Should Clients Expect Before Treatment Begins?

Clear Communication

• Since the focus of the treatment involves working on the gluteals and likely will include the adductors of the affected leg, it’s important to clearly communicate this before the massage begins. In your consent to treat statement, point on yourself to the buttock and inner thigh, explaining that the draping needs to be high to uncover the affected muscles. This may include hiking underwear up, or having the client remove underwear before treatment, with the provision that the area is securely covered with the draping. Whether the client agrees to this plan or prefers that you work through sheets or underwear, be sure that you document this in your treatment notes.

Moderating Pain and Other Symptoms

• Advise beforehand that assessment and treatment may temporarily make symptoms worse, but this should diminish as the work proceeds.

• At times treatment may be uncomfortable; the client shouldn’t have to endure this by holding his breath or clenching his fists to tough it out. It’s ultimately counterproductive to cause tissue to tighten in response to pain.

Remind the client that you can vary the speed or depth of any technique to keep possible discomfort at a minimum. Review diaphragmatic breathing with the client as a method of pain moderation.

General Treatment

Massage is effective when treating piriformis syndrome resulting from soft tissue causes, such as hypertonicity and trigger points, and altered posture, such as hyperlordosis.

Edema in the leg is more effectively treated after compression is relieved in the buttocks. If piriformis syndrome occurs during pregnancy, obviously massage will not remove the cause, but will give temporary relief. Pronation may require referral for orthotics.

If your assessment has shown contributing factors present like anterior pelvic tilt and hyperlordosis, massage for the lumbar muscles and tight hip flexors is appropriate. Clients could be started prone or sidelying for this; for pregnant clients, sidelying may be the only comfortable position.

In sidelying, pillow for comfort and support. A pillow is placed between the knees, supporting the affected leg in a neutral position that avoids internal or external rotation of the femur. If edema is present, use additional pillows to comfortably elevate the ankle. Throughout the treatment, a relaxation and pain reduction focus is important.

Use deep moist heat over the affected buttock while massaging the lumbar region, and after treating trigger points. If edema is present, cool towel wraps are used over the affected area.

Lumbar fascia is treated using fascial techniques. Trigger points in quadratus lumborum can hold the sacroiliac joint dysfunction in place. Sidelying is an ideal position to treat this muscle; the client puts the arm on the affected side above his head while allowing the leg on the same side to drop behind the flexed table-side leg.

| Contraindications Avoid compression of the sciatic nerve, especially if using the elbow at the lateral border of the sacrum. If the client experiences numbness and tingling down the leg to the foot, this could indicate compression of the nerve and the elbow is moved off the area. Joint play, along with hip and sacral mobilizations, are avoided in the third trimester of pregnancy and performed with caution with osteoarthritis or with a degenerative condition affecting the hip or sacrum. Do not perform frictions if the client is on anti- inflammatories. Do not massage locally for 10 days after a cortisone injection. |

This opens the gap between the lower ribs and the ilium, allowing easier ischemic compression into the muscle. Referral patterns from quadratus lumborum refer into the SI joint and lateral hip. Draping over gluteals should be secure yet allow access to as much of the buttock as is comfortable for the client. If the client elects not to wear underwear, precise and secure draping is essential. The gluteal cleft is never exposed. A towel can be used just distal to the iliac crest to secure the sheet from slipping down. A large towel can cover the adductors of the table-side leg.

Before you start specific techniques, remind the client about diaphragmatic breathing to help reduce any painful symptoms that may occur. The slower you go, allowing the tissue to adapt, the less likely you are to cause pain. Intersperse deeper specific work with soothing circulatory strokes.

Initially, use skin rolling and other fascial techniques over gluteals. Then move on to using petrissage over the entire buttock. Work along the iliac crest and the sacrum and around the greater trochanter. All the gluteal muscles are treated thoroughly. Gluteus maximus trigger points refer locally to the buttock, along the SI joint and superior to the ischial tuberosity. Trigger points in the posterior fibres of gluteus medius refer over the sacrum, along the SI joint and the posterior crest of the ilium and into the mid-gluteal area. Gluteus minimus trigger points refer locally and to the posterolateral thigh and calf, in what Travell calls a “pseudo sciatica” pattern (1). Gradually sink through the muscle layers with your techniques.

Piriformis And Sciatic Nerve Landmarks

Piriformis is deep to gluteus maximus. The posterior superior iliac spine on the unaffected side is landmarked and a line is imagined between it and the greater trochanter on the affected side. Piriformis lies deep to this line. Make sure you’re on the muscle by palpating with your fingertips where you think piriformis is. Then ask your client to flex the knee and externally rotate the hip while you resist this action at the medial ankle. You should feel the muscle contracting through the overlaying gluteus maximus. The sciatic nerve may be palpable as it emerges inferior to piriformis, curving laterally around the ischial tuberosity just above the deep lateral rotator quadratus femoris. This area is likely tender.

Piriformis trigger points are at the lateral border of the sacrum and less than one-third of the way medially from the greater trochanter. Referrals are to the sacroiliac region, the buttocks and over the hip joint, sometimes extending over the proximal two-thirds of the posterior thigh. In comparison, pain from the nerve entrapment goes down the posterior thigh to the calf and sole of the foot.Treat both ends of piriformis with specific kneading, progressing to muscle stripping. Trigger points are treated using ischemic compression or other appropriate technique. This is followed with heat and a stretch to the piriformis muscle later in the treatment.

Glide along sacrotuberous ligament with stripping (you can use your elbow with careful landmarking) starting at the ischial tuberosity and moving superiorly toward the sacrum, getting the gluteus maximus attachments.

Post-isometric relaxation (PIR) can also be used starting with a flexed-knee position. Take the femur comfortably into internal rotation, then have the client contract piriformis with ten per cent strength while you resist this action. Ask the client to hold this contraction for 10 seconds, then exhale and relax the muscle completely. You then slowly take the hip further into internal rotation until you hit the next barrier. Repeat the cycle three times. Keep the lumbar spine and pelvis in a neutral position.

Remember, the various actions of piriformis depending on its position? It’s important to treat all its antagonists. Internal rotators such as tensor fascia lata and the anterior fibres of gluteus medius may harbour trigger points; these can be treated in the sidelying position also.

To get to the hip adductors, have the client move into the supine position. Maintain secure draping, especially if working on superior adductor attachments or pectineus muscle.

Also in supine position, a trigger point in psoas muscle that refers into the SI joint can be accessed at the L3 level, just lateral to the spine.

If the SI joint is dysfunctional, joint mobilizations are used at this point. You may wish to finish the treatment with lymphatic drainage if edema is present.

Client Self-care is Vital

- A gentle supine stretch of piriformis has the client’s unaffected hip and knee straight. The hip and knee of the affected side are flexed, and the foot is placed flat on the floor just lateral to the unaffected knee. The client takes the hand on the unaffected side and grasps the flexed knee, pulling the affected leg into flexion and adduction.

- For a standing self-stretch, the client places the foot of the affected side on a chair, with the hip flexed to 90 degrees, and the thigh parallel to the floor, then bends at the waist with the arms loosely reaching towards the floor. The stretch is held for 30 seconds. Then the muscle is stretched farther by bending deeper at the waist and increasing the reach towards the floor.

- A tennis ball is used on gluteal and piriformis trigger points. While lying on the floor or standing against a wall, the ball is placed over the trigger point and the client leans into it, feeling a tolerable discomfort. The referral pattern of the specific trigger point is likely experienced. Position is held until the discomfort resolves. Advise client to avoid compressing sciatic nerve (indicated by numbness/tingling down the back of the leg to below the knee).

- Modify activities. Knees and feet are kept close together when sitting. Positions are changed frequently and breaks are taken during aggravating activities. If sleeping on one side, the client places a pillow between the knees to prevent excessive hip adduction and shortening activation of piriformis trigger points.

- Stretch piriformis before and after aggravating activities or sports. If symptoms are acute, the client may require a break from the specific activity until symptoms are less severe.

- Educate the client about full diaphragmatic breathing for pain management. Yoga and Tai Chi may help with relaxation and stretching.

References

- Travell, Janet G, and David Simons. 1992 Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Vol. 2: The Lower Extremities. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

- Pace, J. B., and D. Nagle. 1976. “Piriform Syndrome.” Western Journal of Medicine. Vol.124: 435-39.

- Dawson, David, Mark Hallett, and Lewis H. Millender. 1990. Entrapment Neuropathies, 2nd. Ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

Print this page