Features

Education

Patient Care

Practice

The down “low” of lower back pain

Reinforcing your practice with assessment

June 12, 2021 By Caleb Fenton

Photos: Nahun Rodriguez

Photos: Nahun Rodriguez Lower back pain (LBP for short) has become a physical condition that disrupts virtually everyone at some point in their lives. Also a redundant topic, you simply Google “low back pain relief” and the numerous articles that follow of how to treat and relieve LBP, becomes almost nauseating. Which articles are true and factual, and what others are more placebos with almost taboo practices. Everyone, in each of their own respectable practice has the “cure” to lower back pain.

To make matters even more construed, LBP can be a sign of more serious conditions and without having some form of an “advanced” understanding, can lead to headaches for a practitioner, because your treatment might make little to no difference or, heaven forbid, worsen your clients symptoms.

Over the years, I have heard many times that the Quadratus Lumborum muscle is typically the culprit to low back pain, second is the hip flexors (specifically the psoas), and coming in third is disc degeneration or herniation. My thought on this is: “based on what assessment?” I have found several causes to LBP and I want to cover a few here, in order to aid your understanding and gain a more open-minded approach when treating clients addressing lower back pain.

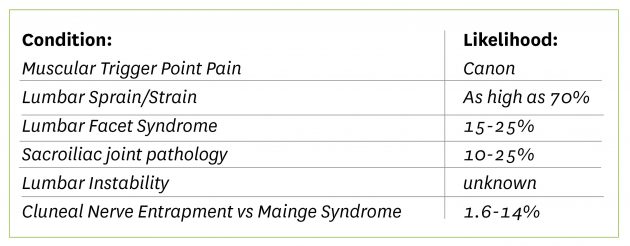

The list of pathologies I aim to review and cover are below:

I am not here to tell you the cure or that I have a new approach to treating LBP. My goal is to help understand how these conditions can present themselves and they may overlap in their symptom presentation. Then, approach your own expression in treating and rehabilitative exercises, in the hopes you’ll make some change.

Muscular Trigger Points

To start simple, muscular trigger points or myofascial trigger points, would be the more common type of discomfort a client may experience. Thank you Travell, Simons & Simons’ Myofascial trigger points! Now myofascial trigger points are common – common in the way that they can be present in several conditions, and can re-create many of the symptoms or even intensify them. With the sign of either decreased range of motion, more local point tenderness to the specific muscular that may cause a radicular pattern, exacerbating their symptoms. Then ischemic compressions, flushing and heat to the area post treatment should help those lower back pains. With little cause to the symptoms and an appropriate screen for other pathologies, this will be one of the more simpler conditions you’ll treat.

Lumbar Sprain/Strain

From chronic trigger points to more acute injuries, we briefly review lumbar sprain/strain injuries. This injury can range in severity showing different signs and symptoms. This can aid in understanding the grade of the injury, adding the levels of healing can change those symptoms and make an incorrect assumption, so it’s ALWAYS important to ask these questions when assuming a lumbar sprain/strain: When did it happen? How did it happen? Was discomfort felt immediately? Did you hear or feel a snapping or popping? Was there any bruising, swelling or redness after the injury?

These few questions alone can help you (subjectively) grade the injury.1 Lumbar sprain/strain injuries is an over stretching injury or when the contractive “call” on the muscle was more than it could handle while in an eccentric state. Onset of this injury can be found in sporting events, heavy and/or awkward lifting jobs, hobbies with more physical contact or motor vehicle accidents.

The client will have a visible contusion which would be deep dark color and speckled red, swelling or heat over the injury sight if they are in a more acute state, noticeable weakness with spinal range of motion testing, difficulty returning to erect from forward flexed trunk which would be present. A Minor’s Sign when the client rises from the chair. A Belt test or ‘Supported Adam’s Test,’ to aid in ruling lumbar or sacroiliac joint pathology.

Lumbar Facet Syndromes

From soft tissue injuries, we move to structural injuries like lumbar facet syndrome and sacroiliac joint pathologies.

“Joint pain is difficult to treat as a RMT, as we specialize in soft tissue injuries.” This is a statement I once told myself and I often hear amongst colleagues. It’s a false statement to believe, what affects the structure is caused by and exaggerated by soft tissue (example of Wolff’s law) and also, massage therapists have the ability to preform low velocity joint mobilization techniques. Even in my own practice, I have heard cavitation with gentle joint play due to the allowance from my soft tissue manipulation. Furthermore, joint traction and rhythmic mobilizations creates a “rest” in the joint capsule and the surrounding supportive structures, which can have an effect on the surrounding musculature.

To start, facet joint irritation in the lumbar spine doesn’t often present with an initial injury or sudden onset. Symptoms might begin mild and gradually worsen over time.2

Jobs with excessive rotation, flexion and extension like construction workers or nurses would commonly be affected, facet irritation can also mimic the referral pattern of sciatic with the subtle difference that it rarely (if at all) cross the knee joint and can also be found along the anterior thigh. They would experience a more diffused deep dull ache, rather than the shooting, zapping pains with associated numbness and tingling from sciatic pain or compressed nerve roots due to disc herniations. With limited range of motion and hesitation to preform actions that place the joint in the closed packed position. Use a Kemps test to rule in, exaggerating local discomfort and a Springing test to segment the vertebra to locate a more specific location of the affected joints.

Sacroiliac Joint Pain

Moving distal we approach the Sacroiliac joint. This condition, according to studies, is often misdiagnosed. Sacroiliac joint pain or SIJP, is often misdiagnosed as radiculopathy (some studies indicate posterior thigh referral that doesn’t cross the knee) and can be difficult to determine and treat. When we ask a client about LBP, they may often mean and without indicating, just lateral and distal to the PSIS. Roughly 80% of individuals will experience an acute flare of LBP, with 10% to 25% of them experiencing SIJP.3 The discomfort would most likely be persistent and worsen during activities causing an inflammatory response that may last a few hours to a few days after activity. Sitting, lying on the same side that is affected, or climbing stairs is a good sign the client may be experiencing Sacroiliac joint pain. Mainly found in adults with a sedentary job and/or lifestyle, the symptom origin may be structural or ligamentous, meaning your client may experience the same symptoms – two different causes with almost the exact same symptom pathology.

So how can we determine the cause, to be sure our treatments hold a positive outcome? Differentiate between a ligamentous causes or a structural one. Both can play off each other as well.

Ask questions that may rule in SIJP, palpate the local structures for sensitivity and perform tests for ligament and joint. Examples of joint testing would be Gaenslen special test, compression test or a Yeoman’s special test. For posterior ligament testing try Hibb’s and for anterior ligament testing try the approximation (distraction) test. These special tests can aid in understand what structures are involved though the symptom pathology would be the same, aiding the direction of your treatment and home care exercises.

Lumbar Instability

Moving forward to instability type pathologies, I want to make an important note that this condition can become a result of severe sprain/strain or the degeneration of the lumbar spine (facet or disc). Essentially the constant dull “nagging” type of discomfort that resulted from the initial injury that didn’t resolve. Treatments to the musculature doesn’t relieve symptoms and can often exacerbate them, due to the muscular tension was aiding stability (muscle guard). The client may even say they don’t feel strong or stable, with a difficulty finding the “center” when sitting or standing. Partial forward flexion of the trunk – like standing over a sink or over the hood of a vehicle, may worsen their symptoms and may avoid said activities altogether.

In any case or cause, your client will often have defeated feelings if they are in a chronic state and manual therapy hasn’t helped or sorrily worsened them and medication only removes the edge.

We start with screening everything else. Check muscles, facets, discs, etc. The unfortunate truth is they all may indicate these pathologies and to the therapist, something won’t add up. Ask them when things began and if there was an initial injury that onset the symptoms. If not, then a gradual degeneration may be the cause to their symptoms.

A good start is range of motion testing, to ask, “can you bend down and touch your toes?” They may refuse to do so, as it may cause too much discomfort. Or they will, and experience a sudden stab or “catch,” in the Lumbar region when they return upright and may even need assistance. This is called an “Instability Catch Sign,” or “Active Flexion Test.” (Different from a Minor’s Sign.) To rule in further, have the client perform a “Prone Instability Test,” this tests has the therapist stabilize the lumbar spine while they perform the test. If all those are positive, strengthening exercises would be more beneficial than massage and possibly a referral for a second opinion and imaging.

Cluneal Nerve Entrapment vs Mainge Syndrome

I finally want to end on a condition that you may not of heard of. Cluneal Nerve Entrapment (CNE), is a not so uncommon condition. The cluneal nerve broken down into three branches; superior cluneal nerve (SCN), middle cluneal nerve (MCN) and the inferior cluneal nerve (ICN). I want to focus on the symptoms on superior cluneal nerve entrapment (SCN-E) that is present in 1.6% – 14%4 of individuals experiencing LBP.

The SCN derives from the posterior rami of the T12 – L3 and innervates the skin of the upper gluteal region. This type of condition you want to keep high in your list of differentials as it has no functional impairment of the lower back and hip. So once you have screened other pathologies, it may be time to investigate SCN-E.

A quick consideration of CNE would be Mainge syndrome/Thoracolumbar syndrome, which is a rare condition affecting the thoracolumbar junction from facet irritation and/or articular capsule due to the facet orientation changes or hypertonic paraspinals. This condition will also affect both ventral and dorsal rami and have more diffuse pain at the lower back, hip and groin. You can screen with a Kemps or Sphinx test that recreates said symptoms.

SCN-E symptoms are a diffuse dull, achy tension in the lower back and refers to the ipsilateral leg, with mild paresthesia to the affected side of the upper buttock. Those symptoms are aggravated by lumbar movements and/or postures. The SCN passes over the iliac crest through the tunnel formed by the thoracolumbar fascia. This is where the entrapment takes place at the osteofibrous tunnel, much like other conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome5. Palpation over the iliac crest that elicits the LBP is a good and exacerbates the symptoms with numbness and radiating pain (tinel’s tap test).

I will say, that at this point nerve block or surgical intervention may be your clients best option for treatment.6 Always consider a second opinion to another healthcare professional. Some articles indicate management with gentle manipulation of the spine to ease load on the nerve roots and massage to the erector spinae group, the latissimus dorsi muscle and thoracolumbar

fascia .7

References:

- Darlene Hertling & Randolf M. Kessler (1996): Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders (3rd edition) , Philadelphia, Penn. (Lippincott). Pg 14-20.

- Darlene Hertling & Randolf M. Kessler (1996): Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders (3rd edition) , Philadelphia, Penn. (Lippincott), Pg 627.

- W.C. Slipman, Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome. Pain Physician. Vol. 4, p 143-152, 2001. ISSN 1533-3159

- Toyohiko Isu, Kyongsong Kim, Daijiro Morimoto, Naotaka Iwamoto. March 15 ,2018. Superior and Middle Nerve as a Cause of Lower Back Pain.

- Tomoyuki Konno, Yoichi Aota, Hiroshi Kuniya, Tomoyuki Saito, Ning Qu, Shogo Hayashi, Shinichi Kawata, Masahiro Itoh. September 20, 2017. Anatomical ethology of “pseudo-sciatica” from superior cluneal nerve entrapment: a laboratory investigation.

- Toyohiko Isu, Kyongsong Kim, Daijiro Morimoto, Naotaka Iwamoto. March 15 ,2018. Superior and Middle Nerve as a Cause of Lower Back Pain.

- William Morgan DC. January 7, 2016. Cluneal Nerve Entrapment: Lumbo-Pelvic Pain (Part Two).

CALEB FENTON, RMT, SMT (cc) has been a massage therapist for nine years and graduated from the Professional Institute of Massage Therapy with honors. He currently practices in a busy multiple disciplinary clinic with other RMTs, physiotherapists and chiropractors in Steinbach, Man., where he lives with his wife and two kids. He has mentored and tutored several massage therapists, and helps with local sports teams to assess and treat athletes. Fenton is currently developing his own seminars to teach massage therapists to find confidence in clinical understanding and practice.

This post was originally published in the Fall 2020 edition of Massage Therapy Canada.

Print this page